Complimentary, but not deep.

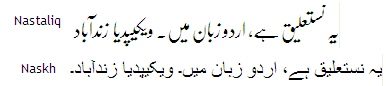

The interwebs widely quote Chomsky saying in Kolkata, in a 10-minute speech in 2001, “The first generative grammar in the modern sense was Panini’s grammar”: An event in Kolkata. Chomsky in fact already said that in the preface of Aspects in 1965: “a generative grammar, in essentially the contemporary sense of this term” . And the final line of The Sound Pattern of English is an allusion to the final sutra of Panini, “ā → ā”.

But as Kiparsky and Staal noted in 1969, Panini’s model of generativity has very different constructs between the two levels: they are derivations, not rewritings. An anecdote on Chomsky’s linguistic theory suggests that Chomsky ended up going back to an approach more like Panini’s with Minimalism in 1991—and might have saved himself 26 years if he’d read Panini more closely when he was citing him in Aspects.

But of course, Chomsky wasn’t learning from Panini, or honing his craft against the Indian master. Chomsky came up with transformations on his own, and merely found it convenient occasionally to allude to Panini as an antecedent. Panini and Chomsky were not undertaking the same research programme, after all.