The photo is a cultural touchpoint as a depiction of harassment of women. It is often cited as such, including on Quora. And people are astonished (including on Quora) to find that the photo was likely not intended as such at all.

I’m throwing the question up to see what others think; what I’m finding, from googling, is no.

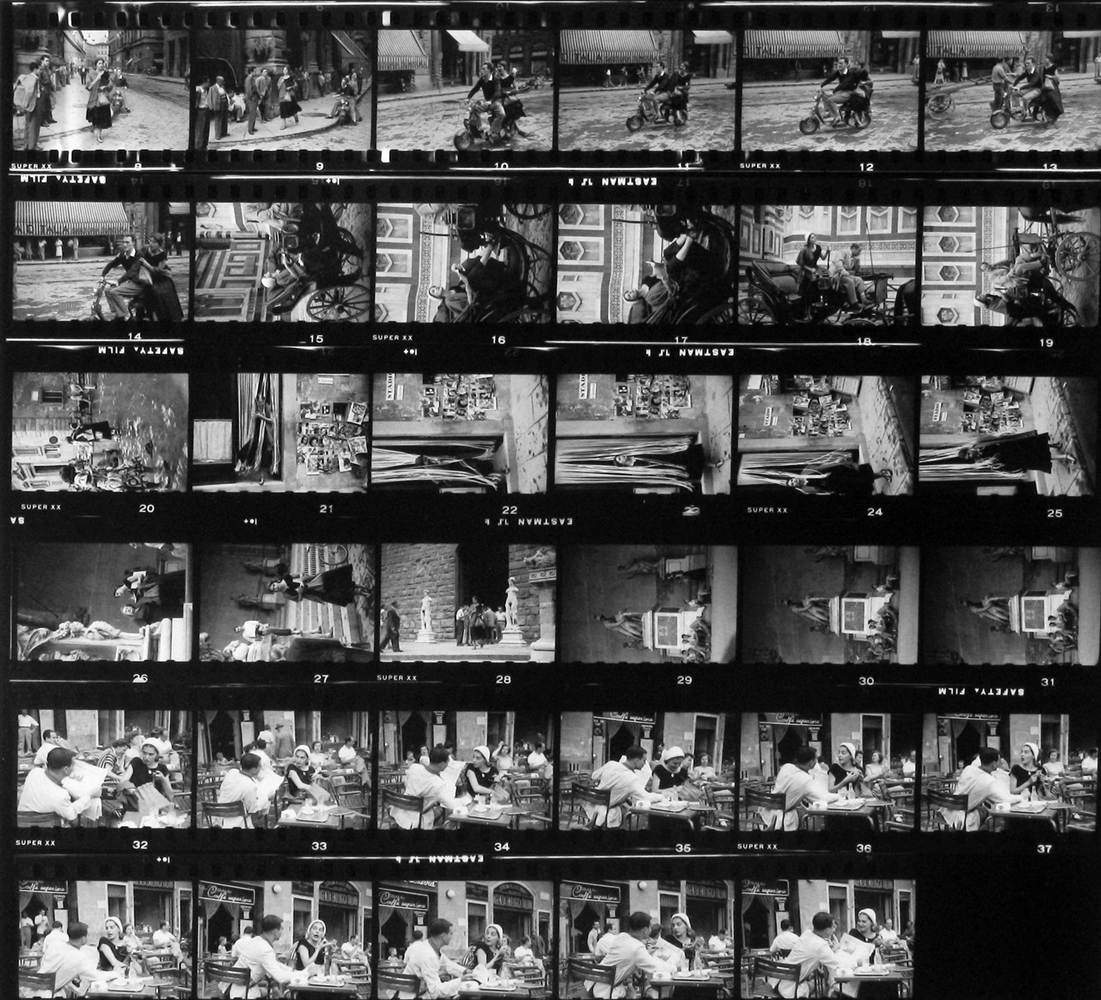

See the following on the series of photos:

American Girl in Italy: Behind the Iconic Photo

The question is opened up by the discussion at Michael Margolies’ answer to What are some of the most widely circulated fake pictures?, between Michael Margolies and Sarah Jansen. As Michael argues, based on the model’s reminiscences (in the link above),

At the time no, if you read what the model writes about the series and this image it’s interesting to see how even her point of view evolves. What she and the photographer wrote about after making the series and what she writes more recently has evolved just as our politics and perspectives have changed.

Sarah retorted with:

So why was she directed to look fearful?

And was not satisfied that the model’s reminiscences reflect what the photographer had in mind.

Well, let’s try and reconstruct what Orkin had in mind from what evidence we have.

Biography : “At 17 years old she took a monumental bicycle trip across the United States from Los Angeles to New York City to see the 1939 World’s Fair, and she photographed along the way.” (Style of Sport features Ruth’s bicycle trip from 1939)

Ruth Orkin: “The photograph was part of a series originally titled “Don’t Be Afraid to Travel Alone.”” (and almost all the other photos in Michael Margolies’ link show Jinx having a ball). The titling was the creator’s.

Orkin’s daughter relates: American Girl

The two were talking about their shared experiences traveling alone as young single women, when my mother had an idea. “Come on,” she said, “lets go out and shoot pictures of what it’s really like.” In the morning, while the Italian women were inside preparing lunch, Jinx gawked at statues, asked Military officials for directions, fumbled with lire and flirted in cafes while my mother photographed her.

Orkin herself relates: Ruth Orkin | American Girl in Italy | The Met

“We were having a hilarious time when this corner of the Piazza della Repubblica suddenly loomed on our horizon,” the photographer recalled. “Here was the perfect setting I had been waiting for all these years…. And here I was, camera in hand, with the ideal model! All those fellows were positioned perfectly, there was no distracting sun, the background was harmonious, and the intersection was not jammed with traffic, which allowed me to stand in the middle of it for a moment.”

From the link American Girl in Italy: Behind the Iconic Photo, Orkin staged a shot with the same model going for a vespa ride with the guy that was leering at her, a few shots before.

My guess about the answer to Sarah’s question? I think Orkin was subverting the notion that the tourist was right to be afraid, in the iconic shot, and her overall message is the “look at the good times you can have as a single female tourist in Italy, if you’re not afraid” theme of the rest of the shoot. With a shout out to her own cross-country adventures at 17 in 1939.

It doesn’t look like the viewer was meant to take the fear any more seriously than the confused squinting:

And in her diary: (An Image of Innocence Abroad), Orkin described the shoot as a “satire”.

The linked article concurs with the analysis:

In its rebirth, however, the photograph was transformed by the social politics of a post-“Mad Men” world. What Orkin and Allen had conceived as an ode to fun and female adventure was seen as evidence of the powerlessness of women in a male-dominated world. In 1999, for example, the Washington Post’s photography critic, Henry Allen, described the American girl as enduring “the leers and whistles of a street full of men.”

You can argue that the sexual politics I’m claiming of Orkin is as naive as you’d expect out of the 50s. But it looks like it’s authentically naive: Orkin may well have thought that she was making a statement for emancipated, empowered single women (like herself and Jinx) travelling the world, and shrugging off the street harrassment.

I mean, you tell me. If that’s not what Orkin had in mind when she had Jinx look scared, then why does she have Jinx on the back of the vespa in the next shot? The resolution is appalling, but she does not look like she’s on the vespa unwillingly…