On seeing this question, I thought, “Huh? Why is this not a question for Wikipedia?”

And then I looked at Wikipedia—English and German and French; and I realised that it’s not as trivial a question as you might think.

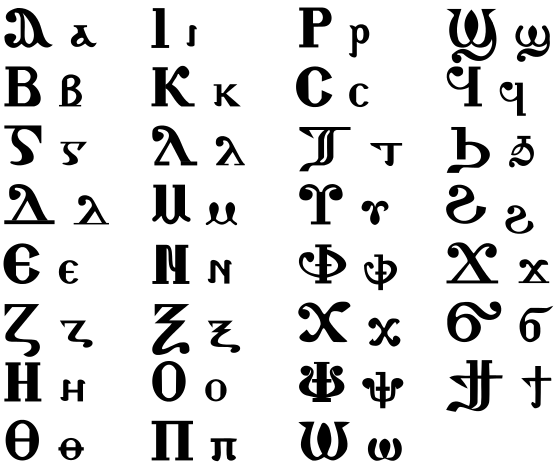

The last three letters of the Coptic alphabet listed on Wikipedia (all three languages) are Ϭ, Ϯ, Ⳁ.

The French and English article on Wikipedia starts with this image:

In this image, that last Ⳁ is missing.

The third last letter, tshēma Ϭ, is a straightforward letter, derived from Demotic Egyptian. It is transliterated as <q> or <tsh>, and pronounced as [kʲ] or [tʃ].

The second last letter, ti Ϯ, is also from Demotic. It is pronounced as [ti] in Sahidic, and [de] in Boharic.

Now, this will immediately throw most people. Coptic grammars calmly say that several letters are equivalents of two other letters: ⲑ is /th/, ⲝ is /ks/, and so forth. But /ti/ is different. If Coptic is an alphabet, then its letters are meant to be either consonants or vowels, but not both. [ti] is not something you find in an alphabet, it is something you find in a syllabary.

The Demotic script that the letter originates, though, was not an alphabet: it was an abjad (consonant-only) script, which meant that single letters often could end up standing for syllables. That ended up happening with ti. And all accounts of Coptic list ti as a normal letter. So a letter it is, even if it is not the kind of letter you expect in an alphabet.

The final letter, Ⳁ, does not have a name or a pronunciation. It is a numeral, with the value 900.

Coptic, like Greek, Hebrew, and (early) Cyrillic, used a different letter of the alphabet for each of 1–9, 10–90, and 100–900. That requires 27 letters. In the case of Greek, which had 24 letters, the numerals for 6, 90 and 900 were represented by archaic letters, that were not considered part of the alphabet normally: ϛ Ϟ Ϡ. Coptic had no shortage of letters, but it still was reluctant to assign numeric values to Demotic letters, as opposed to letters that came from Greek; so it added ⲋ for 6, reused the ϥ for 90 as the letter fai /f/, and came up with Ⳁ for 900.

Does Ⳁ actually count as a letter? The precedent of Greek says no. Alphabet copte — Wikipédia refers to it as a “abbreviating ligature”, which would say no. Coptic numerals only are in common use in the later Boiharic dialect; the earlier Sahidic dialect did not use them, so that is a vote against as well. And the two Sahidic grammars I’ve had a look at, Johanna Brankaer’s and Bentley Layton’s, do not give Ⳁ as a letter. Layton doesn’t even mention Ⳁ until his discussion of numerals.

Wikipedia and Unicode list Ⳁ as a letter of the Coptic alphabet, because they have to list it somewhere; but in the normal Coptic understanding of “alphabet”, Ⳁ isn’t part of it. The atypical ti Ϯ is it.