Contemplating the follies of Quora, as I am wont to do, is an often dispiriting exercise. An Existentialist Parable, as I have called it. An exercise that can made one go all nihilistic.

I’m already warning friends to intervene if they find me muttering “Tear it down, Elias!”

To help them do so, I need to recount what that phrase means.

I’ve just discovered it myself, thanks to Constantinos Kalampokis’ answer to Why do Greeks break plates when dancing? and, independently, Evangelos Lolos at https://www.quora.com/Why-do-Gre…

I could cite Constantinos’ answer, but I’d rather retell the story myself.

The phrase comes from a Greek movie triptych about loneliness, It’s a Long Road (1998). The first two parts of the movie are obscurantist and ruminative, in the way you’d expect of a European arthouse film: a game warden confronted by the shooting of the last midget goose in a national park; an archaeologist stumbling on an ancient tomb of Macedon.

The third part was not as popular with the critics, because its dabbling in Greek low culture makes it stylistically more uneven than the muted first two parts. The third part is nihilistically over the top, and was, quite plausibly, something of a hit with non-arthouse audiences; it even has a Facebook fan page. The YouTube commentariat, vulgar and sexist though they are, are quite unanimous that this film should be taught in school. And they draw parallels with the wasted finances of the 90s, that have brought Greece to where it is now.

But mostly, revelling in the macho nihilism.

The full 40 mins is online. It is a very good film:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=GdXWJi0VSWs

This clip is abridged (10 mins); it doesn’t give enough of the protagonist’s despair, and it emphasises the over-the-topness over the lead up, but it works:

Times given from the 10 min abridgement.

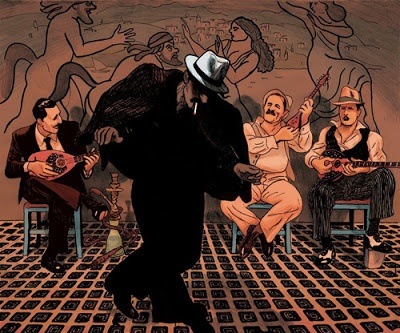

Makis Tsetsenoglou runs a furniture factory in the small town of Kilkis. His wife leaves him and takes the kids. (“Two months ago, you came to my bed and stunk of Bulgarian women.”) The abridgement skips Makis’ shock and isolation, and picks up with Makis heading to the local bouzouki joint, Vietnam, to drown his sorrows. His sorrows won’t drown easy.

He orders rosepetals cast onto the chanteuse (2:30). His sorrows do not drown.

He orders all the plates in the establishment brought to the dancefloor for smashing (3:00). His sorrows do not drown.

He bids the reluctant establishment owner come out (“Why the hell didn’t you tell him I wasn’t in?”), and asks him to bring out whatever glassware can be smashed from the kitchen (4:50). His sorrows do not drown.

As bored Bulgarian hookers look on, the owner comes out to check whether Makis is having a good time (6:00). Why, no, my dear Mr Makis, there is nothing left to smash. All that’s left is the bathroom tiles. Makis turns to him with a smile. The toilet bowls are ceremonially dispatched on the dance floor; he is paying, after all. Yet his sorrows do not drown.

“Tell me. (7:15) How much do you reckon this joint is worth?” “Maybe 20–25 mill?” “Fine, I’ll give you 30 mill, to sell it to me this instant.” “What do you want to do, Makis? Run it?” “Run it? Don’t be stupid. I want to smash it.” His sorrows do not drown, but he does finally start dancing.

The musicians adjourn outside. He signs the check (8:00), and when the owner sycophantically says και το καινούργιο δικό σου, μεγάλε “You can own the rebuilt joint too, chief”, Makis issues one of those ceremonial phrases that Greeks and Turks are renowned for—though this particular ceremonial phrase is original with him: να ’χουμε να γκρεμίζουμε. “May we always have enough money to keep demolishing with.”

He then takes a bottle of whisky, and uses it to set his tie alight to the sound of the bouzouki. He sets his favourite trenchcoat alight, and dances with it.

And at last (9:20) he calls out to his mate: Ρίχ’ το Ηλία! Ηλία ρίχ’ το!

Tear it down, Elias!

A bulldozer comes into view. The bulldozer keeps going, and takes Vietnam nightclub with it. And Makis stumbles, dancing into the dawn.