Not a question I know much about, but let me take a stab, and see if someone more knowledgeable corrects me.

The Wikipedia article on Constantine I goes on to say:

The capture of Thessaloniki against Constantine’s whim proved a crucial achievement: the pacts of the Balkan League had provided that in the forthcoming war against the Ottoman Empire, the four Balkan allies would provisionally hold any ground they took from the Turks, without contest from the other allies. Once an armistice was declared, then facts on the ground would be the starting point of negotiations for the final drawing of the new borders in a forthcoming peace treaty. With the vital port firmly in Greek hands, all the other allies could hope for was a customs-free dock in the harbor.

In this scenario: Bulgaria takes Salonica, and Greece takes a good chunk of (FYRO) Macedonia. In real life, Bulgaria then went to war with Serbia and Greece in the Second Balkan War, dissatisfied with how much territory it had gotten, and Serbia thought that Bulgaria was reneging on the deal they had before the war on what would happen next.

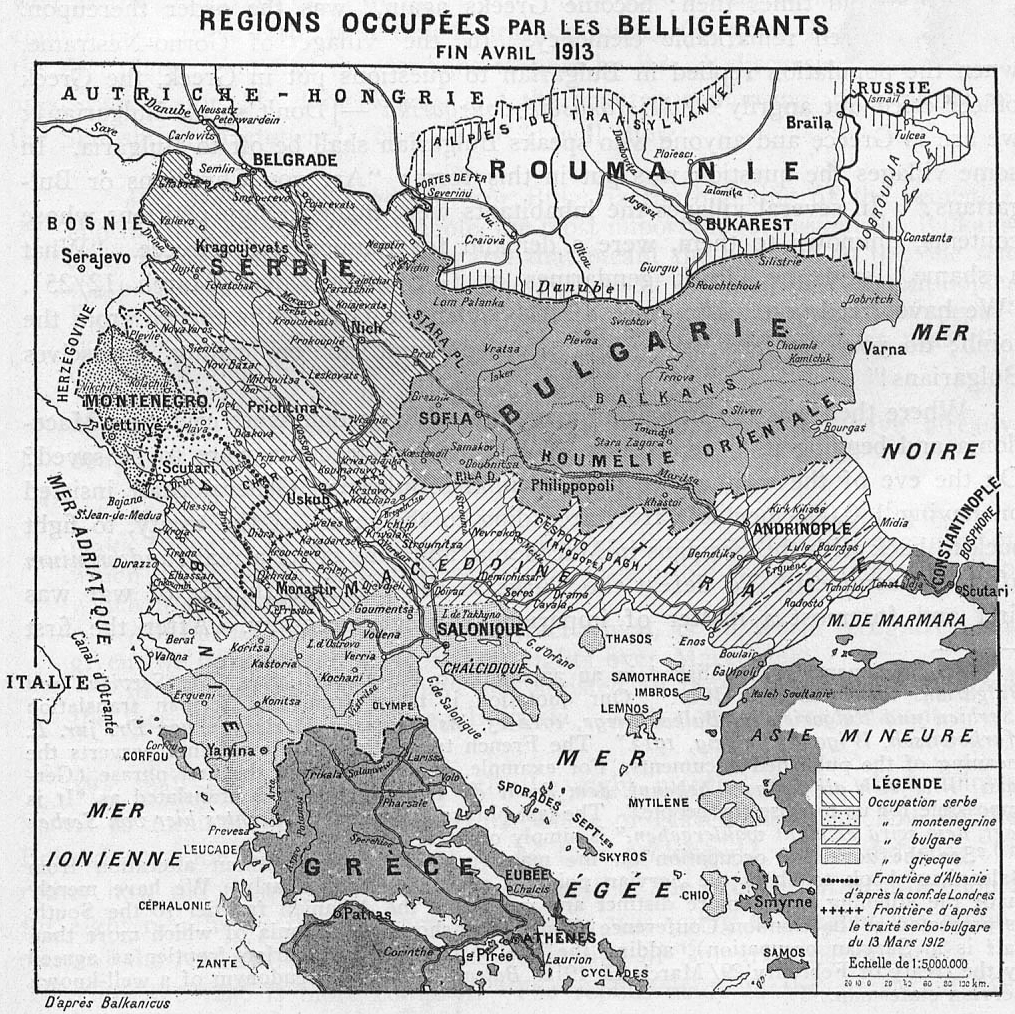

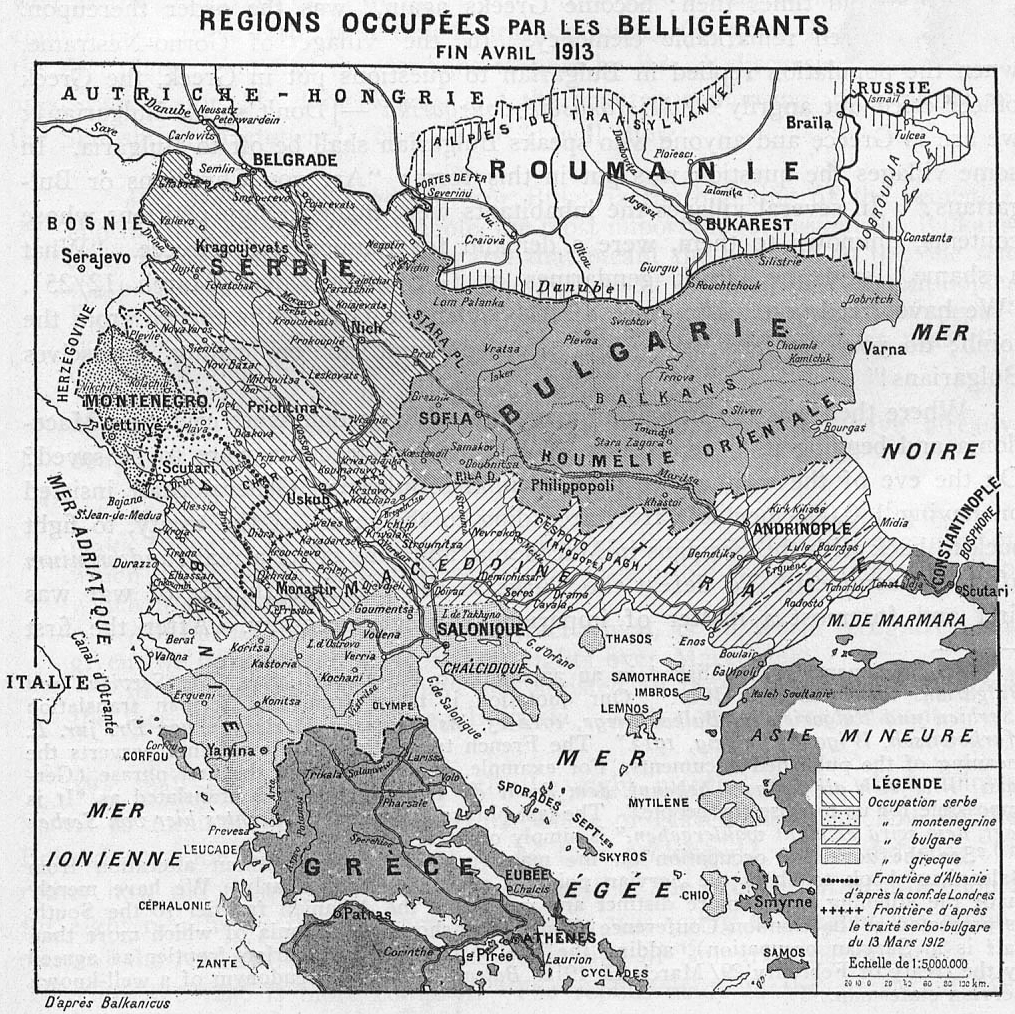

Balkans after the First Balkan War. Bulgaria has gotten a lot bigger than it was later. In our scenario. Constantine I takes Monastir, and loses Salonique in the process.

Greeks having Monastir and not having Salonica spells even more trouble. I would surmise that the Second Balkan War becomes a three way war rather than a two way war. Any deal between Bulgaria and Serbia would be off. Serbia may well feel more of an imperative to protect the Southernmost Slavs, as Greece is now a lot closer to Skopje. Greece can’t be happy with Bulgarians in Salonica, especially as this likely means even more ethnic Greeks under Bulgarian control (Chalkidiki, as well as Eastern Rumelia).

In the ensuing free far all, Bulgaria is at less of a disadvantage: it may have retained Western Thrace, and it may even have ended up taking a big chunk of Vardarska Macedonia—which would end up with all of geographic Macedonia being Bulgarian.

I dunno. You tell me.