The study of language has an -ology word in Greek (unsurprisingly enough): γλωσσολογία /ɣlosoloɣia/, “language-ology”. Italian uses the more Attic version sometimes as well: glottologia.

Beyond those, yeah, linguistics.

The study of language has an -ology word in Greek (unsurprisingly enough): γλωσσολογία /ɣlosoloɣia/, “language-ology”. Italian uses the more Attic version sometimes as well: glottologia.

Beyond those, yeah, linguistics.

Is it poor etiquette? As delineated by Quora’s purpose for the site, no, because they built that feature in, and because the site keeps insisting that it is a Q&A and not a discussion site.

What do I think? What Ben Sinclair said. It’s people’s right to, but I don’t have to like it, and I don’t. Especially the dismissive “if I wanted a discussion, I’d have gone to Reddit” response that I’ve seen from writers like Ernest W. Adams. He’s a great writer, but if he’s not interested in a two-way exchange on any of his answers—well, I’ve increasingly lost interest in engaging with him one-way. Yes, it’s his right to block comments, and yes, Quora is happy for him to. And it’s my right to view it poorly, and “go hang out on Reddit then” is not a meaningful response to that.

See also

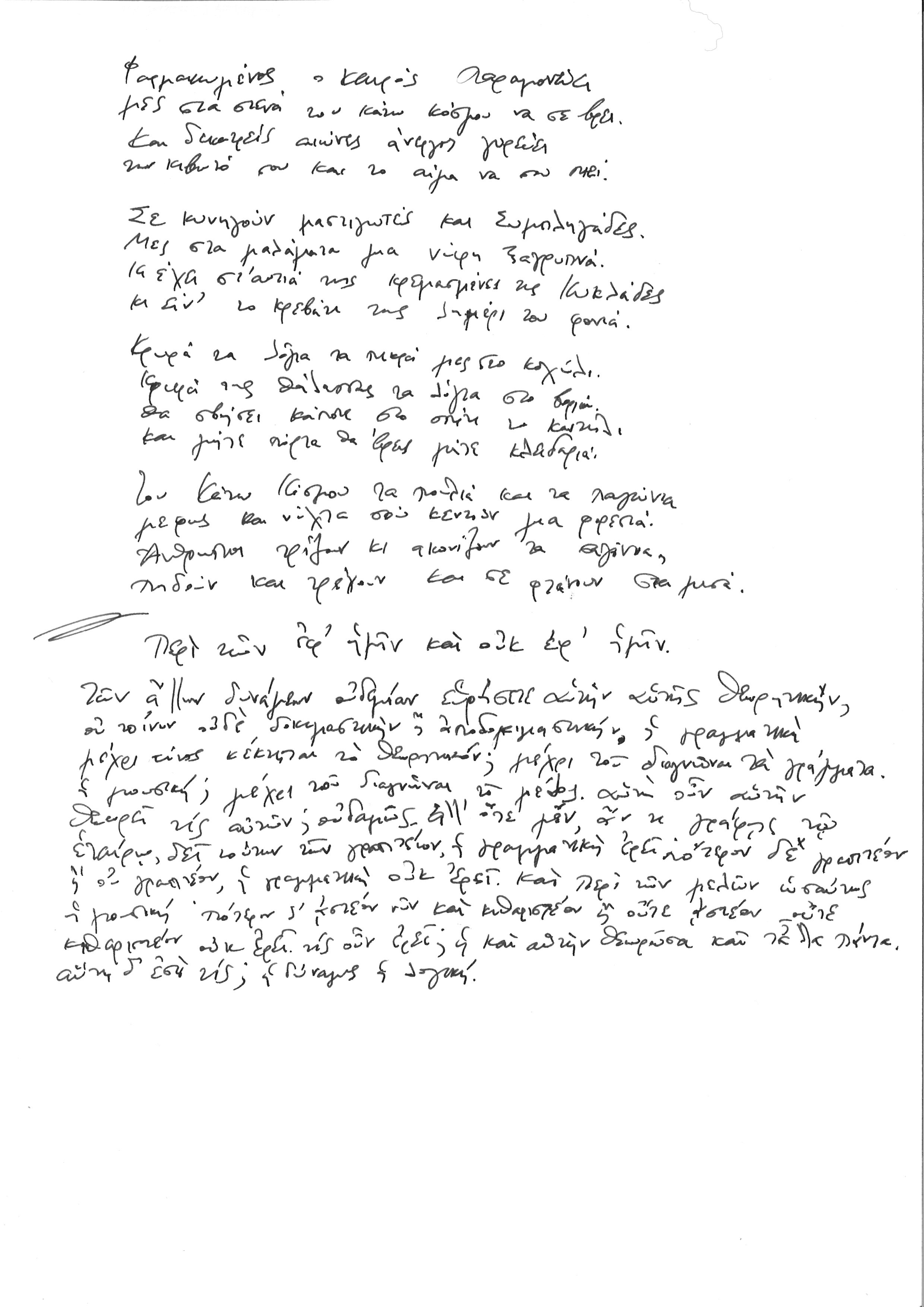

I could say that I’m capable of writing neater than this, but I’d be lying. Twenty years ago: maybe.

Two texts. For modern monotonic, my favourite song lyric, stixoi.info: Του κάτω κόσμου τα πουλιά. For ancient polytonic, the beginning to the Discourses of Epictetus.

No reference needed further than the Wikipedia definition:

words and phrases, such as “me” or “here”, that cannot be fully understood without additional contextual information — in this case, the identity of the speaker (“me”) and the speaker’s location (“here”). Words are deictic if their semantic meaning is fixed but their denotational meaning varies depending on time and/or place. Words or phrases that require contextual information to convey any meaning – for example, English pronouns – are deictic.

then is anaphoric, but it is also deictic: the time that it refers to depends on the time that the speaker is speaking. You could argue that its reference is fixed if it is a historical narrative: “Caesar crossed the Rubicon. Then he began the Roman civil war”—refers to 49 BC whether spoken in 2000 or 2050. But in “I will eat, and then I will go to bed”, the time of the then is quite different depending on when the phrase is spoken, because the clause it references itself has its time anchored on the speaker.

If the deictic centre is not fixed but egocentric, then the expression is deictic, even if it’s primarily anaphoric (as then is). The denotational meaning varies depending on time and/or place.

In tribute to all those Quorans who have given me insight and entertainment and community. Jimmy Liu (gone but never forgotten), Michael Masiello (magister optimus), Robert Todd (elegentiae arbiter), Lyonel Perabo (skis grow out of his shoes), Zeibura S. Kathau (no goddamn amateur), Lara Novakov (#freelaranole), Aziz Dida (asker of neighbourly questions), Philip Newton (my Quora mentor), Joachim Pense (maintainer of standards), Sam Morningstar (knows more than a thing or two), Dan Holliday (the US Jimmy Liu), Brian Collins (get down here soon!), Dimitris Almyrantis (erudite gadfly), Dimitra Triantafyllidou (my northern counterweight), Eleftherios V. Tserkezis (scholar and gentleman).

And all those who’ve been omitted because they’ve been relatively silent lately, or that I’m yet to get to know.

I love youse guys.

Was it Ελένη ?

That would be Helen. Not surprising for a tat…

In Modern Greek, posótita and piótita; in Ancient Greek, posótɛːs and poiótɛːs. So… sure.

But look at what’s actually happening here. The two words are derived from the words for “how much” and “what kind” (in Latin, quant-um and qual-e), plus the affix for nominalising adjectives (Latin –itas). It’s literally “how-much-ness” and “what-kind-ness”. If the affix is a suffix, the words are bound to rhyme, or at least end in the same syllable. In fact, it’s English where they off-rhyme: the consonants after the accent are not identical.

As the other answers show, lots of languages calque the terms with native roots. Thus Albanian sasi and cilësi (I recognise cilë, at least); and Croatian purist kakvoća količina (I recognise kak).

Greek: Someone drunk is, or becomes:

1. στουπί, meaning oakum, or tow:

It’s a traditional society concept, so the modern metaphorical meaning is the main one. Presumably the point is that, like oakum and caulking, you are soaking up a lot of liquid.

τάπα “barrel lid, barrel tap” has the same connotation.

2. τύφλα “blindness”. Fine distinction being made between the adjective τυφλός “blind” and the colloquial noun τύφλα; applied to people, it only means “drunk”, though there is also the expression δε βλέπεις την τύφλα σου “you can’t see your own blindness”, of someone ignorant. Same derivation as “blind drunk”.

3. σκνίπα “gnat”. So drunk as a gnat. Well, Australian English has “pissed as a newt”, so OK.

The wonderful, magnificent, erudite people at SLANG.gr have put together the following list of words referring to inebriation. Some of those will be nonce ad hoc coinages like on Urban Dictionary, but the calibre of SLANG.gr is far higher:

αλοιφή, γκλάβα, γκολ, γόνατα, ζαμπόν, ζάντα,κάκα, κλασμένος, κόκαλο, κομμάτια, κομματιανός, κουδούνι, κουνουπίδι,κουρούμπελο, κώλος, λιάρδα, λιώμα, μανουάλι, μουνί, ντίρλα, πίτα, πλακάκι,σβερκώνω, σκνίπα, σταφίδα, στυλιάρι, στουπί, στρακόττο, τάπα, τούρνα, τούτζι,τσαλμπουράνι, τύφλα, φέσι, φέτα, φσέκι, χώμα.

I’ll mention the words I recognise:

αλοιφή “ointment”, γκλάβα “(informal) head (Slavic glava), γκολ “soccer goal”, γόνατα “knees”, ζαμπόν “ham”, ζάντα, κάκα, κλασμένος “farted”, κόκαλο “bone; (slang) frozen in place, of someone shocked”, κομμάτια “in pieces”, κομματιανός, κουδούνι “bell”, κουνουπίδι “cauliflower”, κουρούμπελο, κώλος “arse”, λιάρδα, λιώμα “molten, pummelled”, μανουάλι “candelabra”, μουνί “cunt; (metaphorically) a mess”, ντίρλα, πίτα “pita”, πλακάκι “tile”, σβερκώνω, σκνίπα “gnat”, σταφίδα “raise”, στυλιάρι, στουπί “oakum”, στρακόττο, τάπα “barrel lid”, τούρνα, τούτζι, τσαλμπουράνι, τύφλα “blindness”, φέσι “fez”, φέτα “feta; slice”, φσέκι, χώμα “dirt; (metaphorically) pummelled, cf. λιώμα)

EDIT: I’m not following all the links, but I like the goal one:

γκολ – SLANG.gr. “I’m goal”, the speculation is, is a corruption of earlier Greek slang είμαι γκον “I’m gone”, where gone is borrowed from English.

An attempt at a grand unified theory of filotimo.

Eleftherios V. Tserkezis touches on all the key aspects.

It is a Greek’s sense of honour, to use the old fashioned wording; of being respected in society, of social capital. It is what one can take pride in as an engaged member of society.

But this particular sense of honour is not tied up with chastity (as timi is): it correlates with discharging one’s social obligations; one gains honour by doing one’s duty. By meeting the social contract.

And one’s duty consists, to a large extent, of positive politeness strategies: of being considerate (hence the touchiness) and (more importantly) being generous.

There isn’t a simple translation, but I guess “being righteous” in some variants of English comes close.

An a-filotimos person, someone without filotimo, is ungrateful and/or ungenerous. There is a clear sense that, by doing so, this person violates the social contract.

EDIT: and filotimieme, to filotimo oneself, is to volunteer something as expected by the social contract. “He didn’t filotimo himself to offer any help” = “He didn’t bother offering any help, as the social contract demands”. This encompasses financial contracts too: an employee who isn’t doing their job conscientiously is also not doing filotimo.

Adrian Beale has the right answer. We’re quite used to people with different accents. The divide is more about international students not having the confidence to associate with the locals, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Reach out to locals, and they will befriend you; no need for the accent. We do judge, but we judge on demeanour, not on accent.

In my day (early 90s), the International Students numbers were lower—which meant that it was more difficult for international students to segregate. My main social group during Engineering, as it turns out, was East Asian. The group included people with Ocker accents (from the country), people with the East Asian variant of Received Pronunciation, and people with more clearly Chinese accents. In retrospect, I realise that I did not have a clear idea who was just off the boat, who studied here in high school, and who was descended from Chinese who came to the goldfields in the 1850s. (My money was on the Ocker sounding guy.)

It was clear that the group was mainly East Asian, plus one Greek (me) and one Fijian Indian. It was also clear that I wasn’t unwelcome, and that the group was not particularly insular. There was a countergroup of Anglos, who didn’t associate socially with the East Asian group, but certainly didn’t shun them either.