Yes. It was never written unaccented, because it was never treated as a clitic. On the other hand, the unstressed variant κι was indeed never accented.

Category: Uncategorized

What does this emoji mean “U0001f60b”?

There are several online dictionaries of emoji meanings.

The intended meaning of [math]unicode{x1f60B}[/math] is “Face Savouring Delicious Food”, which is the Unicode name of the emoji.

U0001f60b Face Savouring Delicious Food Emoji (Emojipedia) offers “Used to indicate a silly happiness; goofy; hungry.”

U0001f60b (Urban Dictionary) offers “thirsty; desperate”

Face Savouring Delicious Food Emoji (Emojibase) notes that :yum: is used in some phones as an abbreviation.

A Google perusal suggests that the “food” association is prevalent.

What would be your response if a famous Quoran replied to you?

I’m not the starstruck type normally, and I’ve grown both more confident and more jaded the longer I’m on here. I did PM “Thank you for following me!… But why?” to a few people in my time: Kate Scott, Jeremy Markeith Thompson, Sabrina Deep, Buster Smith.

Early on, I was proud to get a comment from Dan Holliday, but my answer was as courteous to him as if he’d had two followers. I may very occasionally still say I appreciate the attention, in my response to a famous Quoran, but I think the more jaded I get, the less it registers; I tend to appreciate reactions equally by people I don’t know, and more by people I do. 🙂

Where can one find the obscure works (i.e. plays and poems) of Nikos Kazantzakis (“Julian the Apostate”, “Odysseus”, “Tertsinas”, etc.)?

In Greece, it’s not particularly difficult to find all the works of Kazantzakis in any middling bookstore; and bless you for mentioning the Terza Rimas, that I have a lot of affection for.

In the Anglosphere, a university with a Modern Greek teaching program will have them. A university that used to have a Modern Greek teaching program, like the University of Melbourne, will have banished them to storage.

From Nikos Kazantzakis – Wikipedia, I see a lot of translations of the more obscure works have appeared in very obscure places—literary journals in the 1970s, limited edition runs of 140. Neither Julian nor the Terza Rimas have been translated, although the Terza Rima I use as one of my email .sigs has been:

- Christ (poetry), translated by Kimon Friar, “Journal of Hellenic Diaspora” (JHD) 10, No. 4 (Winter 1983), pp. 47–51 (60).

You can download that issue at: Issues 1-2, 3, 4

Will Brooke Taylor ever be unbanned?

The time frame for appeals, we are told, is two weeks. See e.g.

- Sierra Spaulding’s answer to How long does it take for Quora to un-collapse an answer?

- McKayla Kennedy’s answer to How long do Quora moderators take to respond to appeals and reported issues?

- Laura Hale’s answer to How long does Quora take to respond to an appeal to anonymity suspension?

- Laura Hale’s answer to How long should I expect to wait for a response from Quora moderation?

Any unbans I have seen have been within that timeframe.

Brooke was banned two weeks ago.

I doubt it.

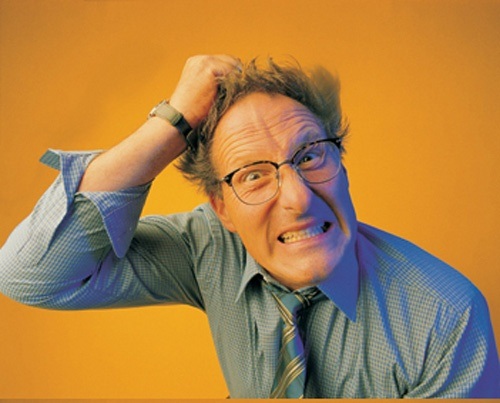

trichotillomania

The Magister’s comment to Nick Nicholas’ answer to Do you find Thucydides hard to read in Greek?

https://www.quora.com/Do-you-fin…

I feel your pain. I am sorry to report that’s just Thucydides talkin’, too. Try reading Pericles’ famous speech if you want to develop trichotillomania.

I understood the word, and now, you will too:

Trichotillomania (TTM), also known as hair pulling disorder, is an impulse control disorder characterised by a long term urge that results in the pulling out of one’s hair. This occurs to such a degree that hair loss can be seen. Efforts to stop pulling hair typically fail. Hair removal may occur anywhere; however, the head and around the eyes are most common. The hair pulling is to such a degree that it results in distress.

The disorder may run in families. It occurs more commonly in those with obsessive compulsive disorder. Episodes of pulling may be triggered by anxiety. People usually acknowledge that they pull their hair. On examination broken hairs may be seen. Other conditions that may present similarly include body dysmorphic disorder, however in that condition people remove hair to try to improve what they see as a problem in how they look.

Treatment is typically with cognitive behavioral therapy. The medication clomipramine may also be helpful. It is estimated to affect one to four percent of people. Trichotillomania most commonly begins in childhood. Women are more commonly affected than men. The name was created by François Henri Hallopeau in 1889, from the Greek θρίξ/τριχ- thrix meaning “hair”, τίλλειν tíllein meaning “to pull”, and μανία mania meaning “madness”.

I find the fact that medicos abbreviate it as TTM adorable.

I plan on retaining my full hair of head for a while longer…

No, don’t you dare.

Thucydides’ Greek is notoriously difficult, but the language of Pericles Funeral Oration is considered by many to be the most difficult and virtuosic passage in the History of the Peloponnesian War.

I mean it!

Οἱ μὲν πολλοὶ τῶν ἐνθάδε ἤδη εἰρηκότων ἐπαινοῦσι τὸν προσθέντα τῷ νόμῳ τὸν λόγον τόνδε, ὡς καλὸν ἐπὶ τοῖς ἐκ τῶν πολέμων θαπτομένοις ἀγορεύεσθαι αὐτόν. ἐμοὶ δὲ ἀρκοῦν ἂν ἐδόκει εἶναι ἀνδρῶν ἀγαθῶν ἔργῳ γενομένων ἔργῳ καὶ δηλοῦσθαι τὰς τιμάς, οἷα καὶ νῦν περὶ τὸν τάφον τόνδε δημοσίᾳ παρασκευασθέντα ὁρᾶτε, καὶ μὴ ἐν ἑνὶ ἀνδρὶ πολλῶν ἀρετὰς κινδυνεύεσθαι εὖ τε καὶ χεῖρον εἰπόντι πιστευθῆναι.

AAAAARGH!!!

(Actual shots of TTM are actually pretty disturbing…)

Are there any dialects of Greek that Nick Nicholas can’t understand?

First up, my vanity is well gratified!

Well, there’s the question, and then there’s the details.

Can I understand someone speaking modern Tsakonian, or read ancient Arcadian and understand it, sight unseen?

Mate, I struggled to understand the Cypriot of my cousin’s husband Fotis; and I have no idea what Homer is on about. Homer!

I’m a really bad example, because I’ve approached Greek as a linguist rather than a classicist, so I’ve learned only the bits I’ve needed. I know that when I was studying my thesis on Modern Greek dialect, I was familiar enough with Pontic that I could read it without a problem, and I probably could hold a conversation in Tsakonian. It’s patchier 20 years on. And I would still struggle with Cypriot basilect, or Samothracian.

Ditto Ancient Greek, and that’s exacerbated by my imposter syndrome. I can kinda understand Attic, but I will sneak peeks at the dictionary when I don’t think you’re looking, and I ain’t touching no Thucydides. I know the Doric shibboleths, so I can probably deal with the Doric in Aristophanes and Archimedes; maybe not Alcman and Theocritus. I did intensive work with Alcaeus and Sappho, so I’m better than the usual classicist on Aeolic. But, because the TLG lemmatiser already dealt with Homer and Herodotus, when I first obtained it as Morpheus from Perseus, I never needed to brush up on my Epic/Ionic.

And non-literary dialects? I’ve read the handbooks of Ancient Greek dialect, such as Thumb and Buck and Bechtel, so I’ve *seen* North-West Greek and Arcadian and Cretan. Understand them? I’d be struggling. I’d pick out a few words more than the average classicist, perhaps, but that wouldn’t be enough for me to do a translation viva.

Edward Conway brings up Linear B in comments, and I’m just going to pretend I didn’t hear him. 🙂

Now, to go to your details: can you triangulate dialects (let alone intermediate stages of the language) from Attic Classical Greek + Standard Modern Greek?

Intermediate stages: Usually. Dialects: Less so.

We don’t have as much Greek attested between Attic and Early Modern Greek as you might think, because most people tried to write Attic. (A very artificial Attic.) Koine is not really challenging if you know Attic; you’ll be relieved at the simplifications, and the occasional Doric-looking words won’t throw you. The papyri are as much Greek as a Foreign Language as they are Koine, but they won’t really throw you either. In between the papyri and Early Modern Greek, we have bits and pieces: snatches of songs, inscriptions written by Greek POWs under the Bulgars. Again, no problem.

Actual Early Modern Greek starts 1100, more or less. There are going to be some archaic words and grammatical usages that will throw you a bit more, if you’ve got just Attic and SMG, and you want to be on the alert for false friends. You’ll understand the gist of things, but you may miss the fine print.

When I co-translated a poem written in 1364 (An Entertaining Tale of Quadrupeds), we looked up every single word in the Early Modern Greek Dictionary, because there were a lot of words that changed in strange ways. The modern word for “pew” for example, στασίδι, was just the mediaeval word for “a spot”: the Rat went back to his spot in the assembly, not to a church pew. The future tense looked very different from Modern Greek, with the modern form originating only in the 1400s, and not really settling down until the 1700s; so you could be missing some nuance there. Prepositions also worked slightly differently.

But honestly, most of the difficulty you’ll find in Early Modern Greek will be dialectal, rather than chronological. If you’re going to read Early Modern Greek, you’re going to find a lot of Cretan material in particular. Dialects are often archaic in some ways, but just knowing Ancient Greek isn’t going to be enough to work them out.

As a little sampler: here’s one of the very few private unlettered letters we have preserved in Early Modern Greek, from 1420 Crete.

Manuel Chantakites, Away from Crete, 1420

Chantakites: Linguistic analysis

I’m curious how easy Greek Quorans—particularly those unfamiliar with Cretan dialect—find it to read.

More negativity

This is a topic about a user who has been banned, and who has just deleted their account (and, I take it, their topic).

Perhaps… the user had some very negative followers.

Very negative:

Bug? Or… feature!

Do dogs understand the concept of dance?

I will not be confused with an ethologist. But I do know that whenever I try to dance with my honey, and our dog is anywhere near, Jenny gets excited, wags her tail, and jumps on us to join in.

Fricking dog.

My understanding with what little I know of ethology is, Jenny does so because she understands dancing as equivalent to dogs’ play-fighting. That, she understands; that’s why she wants to join in. So I’d assume that’s the shortcircuit in her brain, rather than understanding dance on its own terms.

Dogs are also hypersensitive to changes in people’s gait. Jenny gets very agitated when she sees me on a swing; but that’s something I gathered from reading, rather than from Jenny. I think the freakout of dogs seeing the changed gait of dancers would overrule any recognition of controlled gait as communication.

How many letters does Unicode currently include in the Latin script, no matter the language, but ignoring upper vs. lower case differences?

Latin script in Unicode – Wikipedia

As of version 9.0 of the Unicode Standard, 1,350 characters in the following blocks are classified as belonging to the Latin script

Let’s remove the uppercase letters; and that leaves us with your answer. From eyeballing:

26+30+128+104+14*8+12+12+67+26 = 517

That leaves 833.

If I’m wrong, I’m not wrong by much.

EDIT: Derek Zech’s answer to How many letters does Unicode currently include in the Latin script, no matter the language, but ignoring upper vs. lower case differences? leaves out more letters than I do, is more thorough, and he sounds more correct. Go upvote him: Vote #1 Derek Zech.