I’ll give a general rather than a specific answer.

The Great English Vowel Shift is a celebrated instance of a Chain shift, a sound change with impacts several sounds one after the other, as a kind of chain reaction.

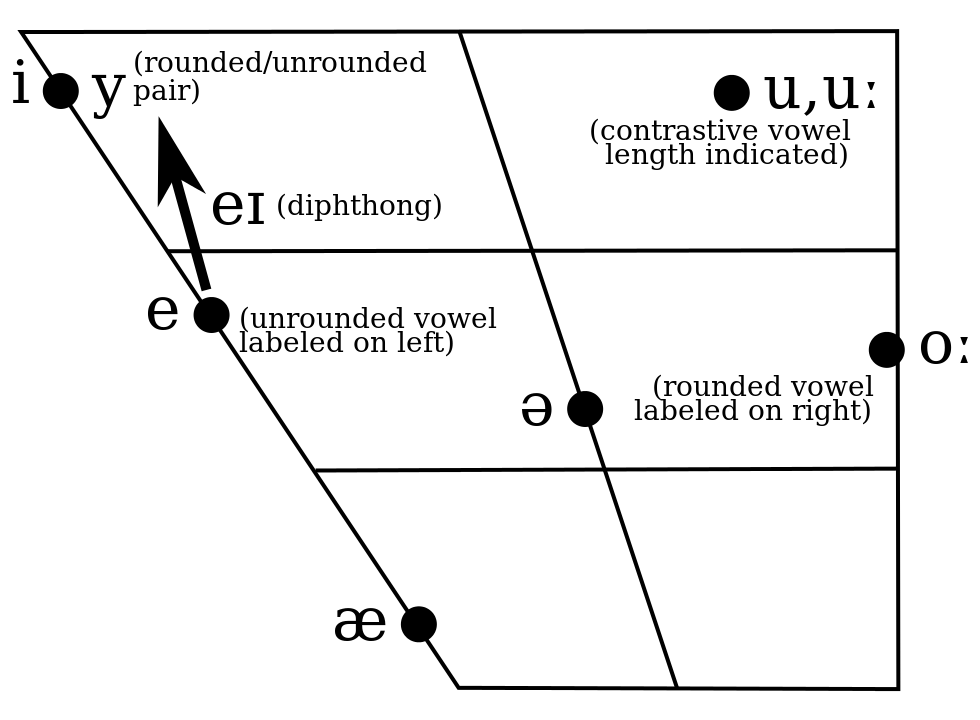

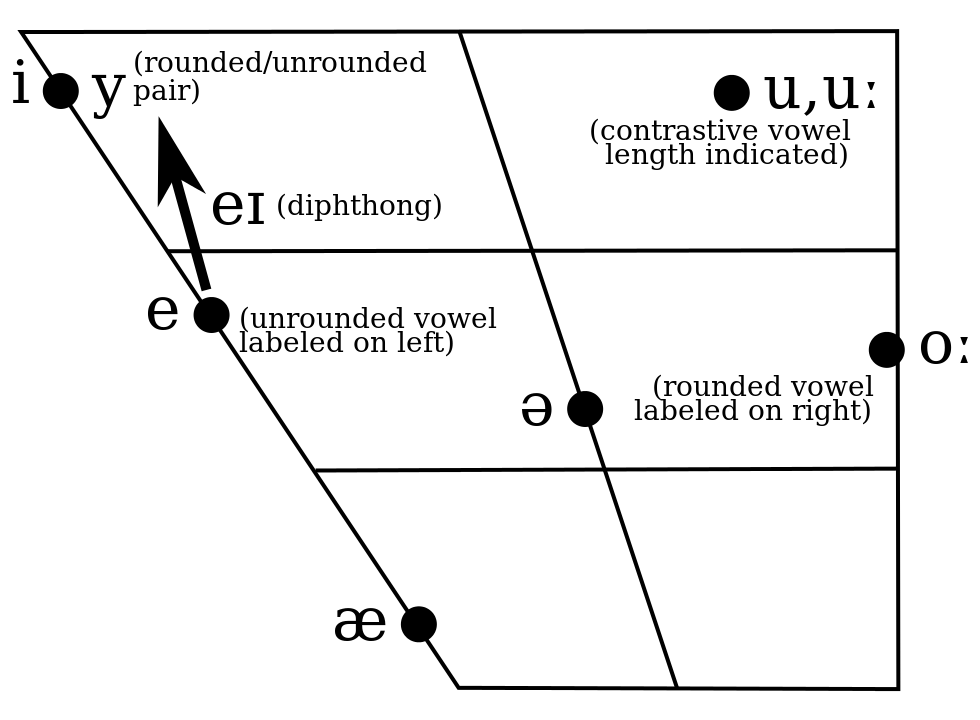

It helps when discussing vowel changes (which are particularly susceptible to chain shifts) to have a Vowel diagram in your head.

There are two different possible sequences of chain shift, and each has its own likeliest motivation.

A push chain involves one vowel shifting so that it becomes ambiguous with another vowel. Because language is used for communication, and ambiguity is a horrid thing, that second vowel moves out of the way: the one vowel pushes the second vowel. But that second vowel now becomes ambiguous with a third vowel. And so on.

In this scenario, mate stops being pronounced [maːt], and starts being pronounced [mɛːt]. But that makes mate ambiguous with meat. So meat stops being pronounced as [mɛːt], and starts being pronounced as [meːt]. Only that now makes meat sound like meet. So meet stops being pronounced as [meːt], and starts being pronounced as [miːt]. Only now meet sounds just like mite. So mite is pushed over the edge, and starts being pronounced as [məit].

(Yes, Early Modern English was pronounced differently to modern English.)

This is an attractive way of understanding chain shifts. But it’s not what the evidence suggests. English, after all, has an astonishing tolerance of ambiguity.

If it didn’t, then how come meat and meet are now pronounced identically?

The second possibility sounds less plausible, but is in fact likelier.

In a pull chain, one vowel moves further away from another vowel. This makes the vowel system of the language seem somehow unnatural to learners: there’s a great big gap where that vowel used to be. So the next vowel moves up to take its place: it is pulled along by the first vowel. That in turn creates a new gap, and the next vowel along is pulled along to take the second vowel’s place.

In this scenario, mite stops being pronounced as [miːt], and starts being pronounced as [məit]. So now, you don’t have an [iː] vowel in English any more: the sequence goes [aː, ɛː, eː, əi]. To fix that gap, what used to be [eː] turns into [iː]: meet now shifts from [meːt] to [miːt]. And then meat [mɛːt] changes to [meːt], to address the absence of an [eː]. And then mate changes from [maːt] to [mɛːt], to make up for the absence of an [ɛː].

And now you’re missing an [aː] sound in English, but hey, what do you want from me. /ar/ has ended up addressing that gap, in any case.

It sounds a lot less sensible—people changing vowels not for some communicative need, but to fit some bizarre arrangement along a trapezoid that only linguists have heard of. But it does seem to fit the facts better.

For example, New Zealand English is having a merry old vowel chain shift of its own happening right now.

And where did it start? Why, with the vowel shift that is the most stereotypically associated with New Zuhluhnd Unglush. The other vowels that have shifted, you actually have to talk to Kiwis to be aware of.

And what is the vowel shuhft thet uz the most stereotuhpically essociated wuth New Zuhluhnd Unglush?

/i/ > /ɨ/.

Remember? mite stops being pronounced as [miːt], and starts being pronounced as [məit]. New Zealand English is doing the same chain shift, only with short vowels.