One might argue that the phonological inventory of Gothic is a spectacularly bad match for that of Modern English. But then again, so was the phonological inventory of Latin.

I think you can, so long as you hold your nose and write vowels as a one to one match with Modern English; you’re not really going to get anything sensible otherwise.

- /f/ and /v/ aren’t differentiated, and they weren’t differentiated in Old English either; we could write <v> as <f>, or <u> or <w> or as <90> (which is a spare letter).

- No <tʃ> (our <ch>), and not much of a soft <c> either. We can press the <x> character into service for one or both.

- No /dʒ/ (our <j>; the Gothic <j> is our <y>). We could give up and make <j> ambiguous between /dʒ/ and /j/, or we could write /w/ as <ƕ> (wh), reuse <w/y> for /j/, and move <j> to /dʒ/. Yuck.

- No /ð/, but that’s ok, <th> is already ambiguous within English.

- No /ʃ/, just as there isn’t one as a letter in English (<sh>). I guess we won’t avoid h-digraphs after all.

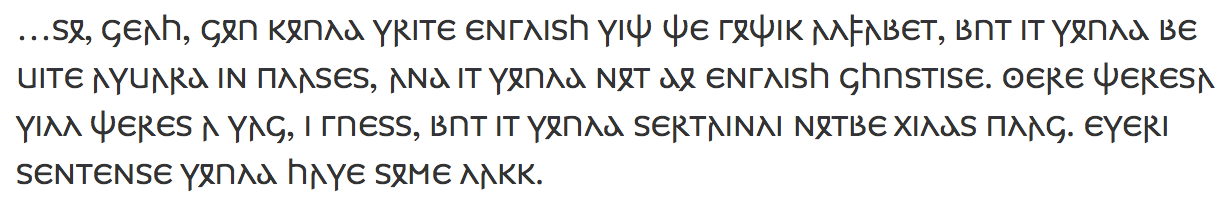

… So, yeah, you *could* write English with the Gothic alphabet, but it would be quite awkward in places, and it would not do English justice. Where there’s a will there’s a way, I guess, but it would certainly not be child’s play. Every sentence would have some lack.

Or, to put that last paragraph in Gothic:

… so, jeah, jou kould write english wiþ þe goþik alfabet, but it would be qite awqard in plases, and it would not do english jhustise. ƕere þeres a will þeres a waj, i guess, but it would sertainli not be xilds plaj. eweri sentense would hawe some lakk.

[math]unicode{x2026} unicode{x10343}unicode{x10349},[/math] [math]unicode{x1033E}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10337},[/math] [math]unicode{x1033E}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}[/math] [math]unicode{x1033A}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10344}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10334}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10332}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10337}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10338}[/math] [math]unicode{x10338}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10332}unicode{x10349}unicode{x10338}unicode{x10339}unicode{x1033A}[/math] [math]unicode{x10330}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10346}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10331}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10344},[/math] [math]unicode{x10331}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10339}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10331}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10335}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10344}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10330}unicode{x10345}unicode{x10335}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10339}unicode{x1033D}[/math] [math]unicode{x10340}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10343},[/math] [math]unicode{x10330}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10339}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10349}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10333}unicode{x10349}[/math] [math]unicode{x10334}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10332}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10337}[/math] [math]unicode{x1033E}unicode{x10337}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10344}unicode{x10339}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10334}.[/math] [math]unicode{x10348}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10338}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10343}[/math] [math]unicode{x10330}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10339}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x1033B}[/math] [math]unicode{x10338}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10343}[/math] [math]unicode{x10330}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10330}unicode{x1033E},[/math] [math]unicode{x10339}[/math] [math]unicode{x10332}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10343},[/math] [math]unicode{x10331}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10339}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10343}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10344}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10339}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10339}[/math] [math]unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10349}unicode{x10344}[/math] [math]unicode{x10331}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10347}unicode{x10339}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}unicode{x10343}[/math] [math]unicode{x10340}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10330}unicode{x1033E}.[/math] [math]unicode{x10334}unicode{x10345}unicode{x10334}unicode{x10342}unicode{x10339}[/math] [math]unicode{x10343}unicode{x10334}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10344}unicode{x10334}unicode{x1033D}unicode{x10343}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10345}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033F}unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10333}[/math] [math]unicode{x10337}unicode{x10330}unicode{x10345}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x10343}unicode{x10349}unicode{x1033C}unicode{x10334}[/math] [math]unicode{x1033B}unicode{x10330}unicode{x1033A}unicode{x1033A}.[/math]