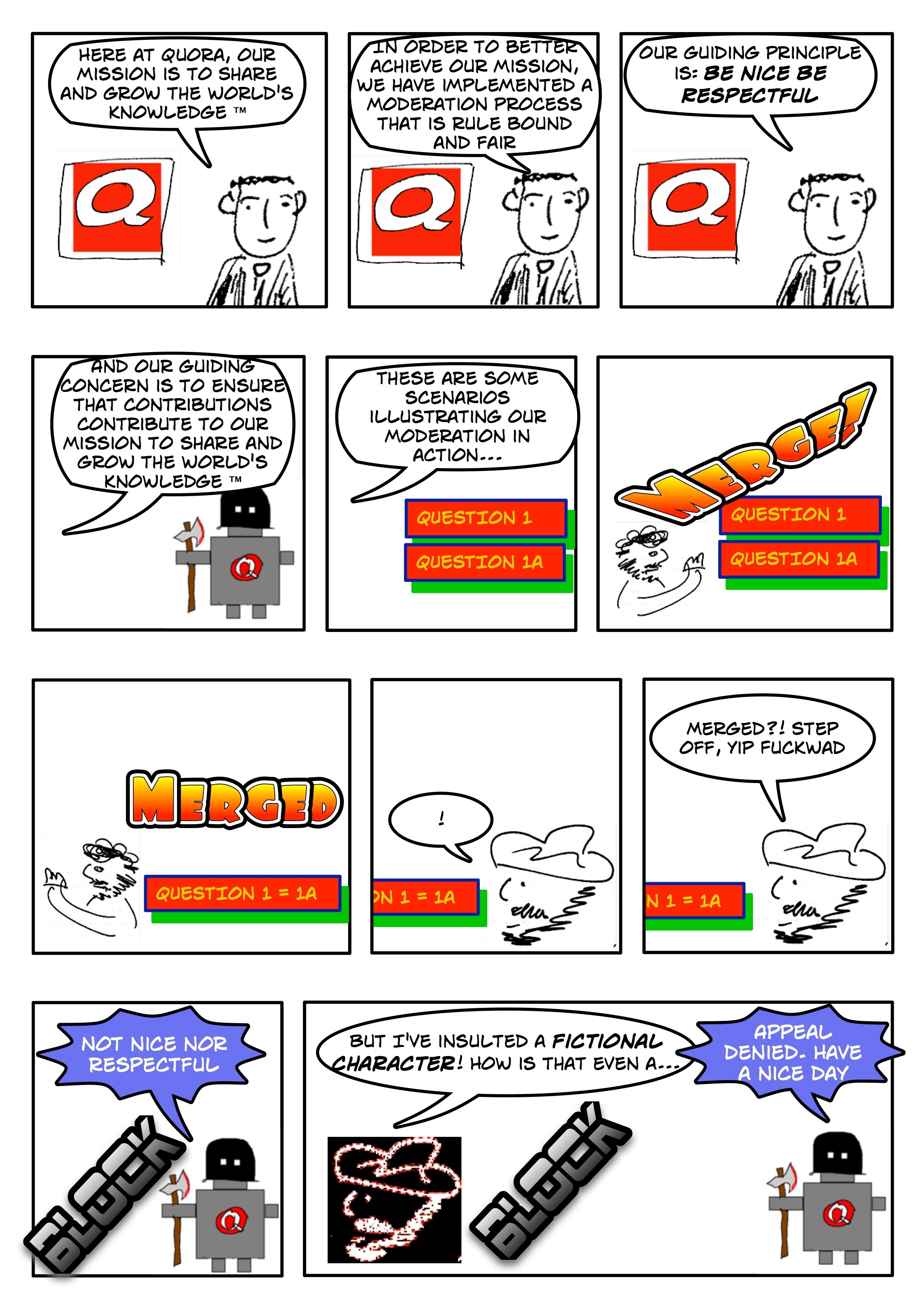

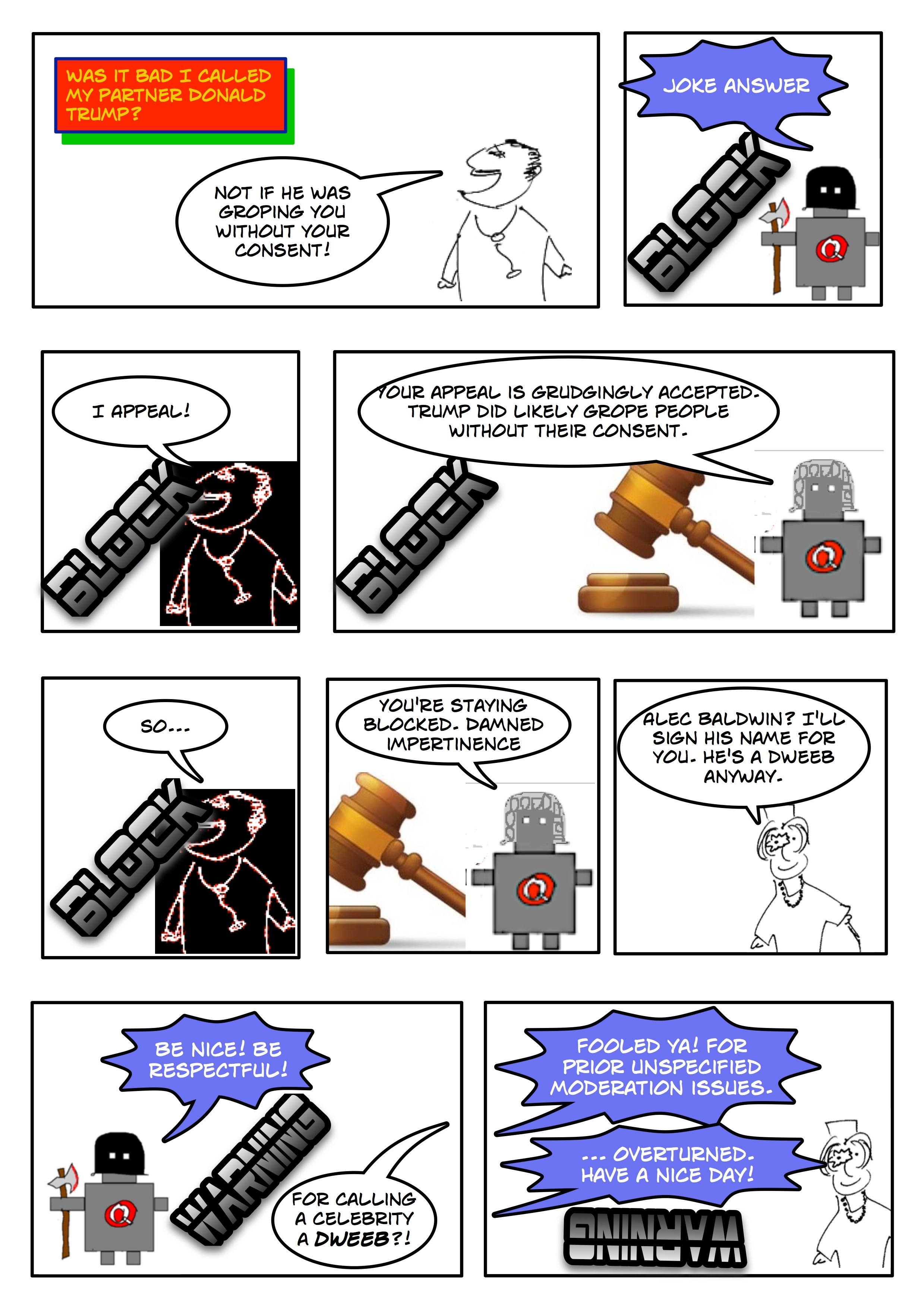

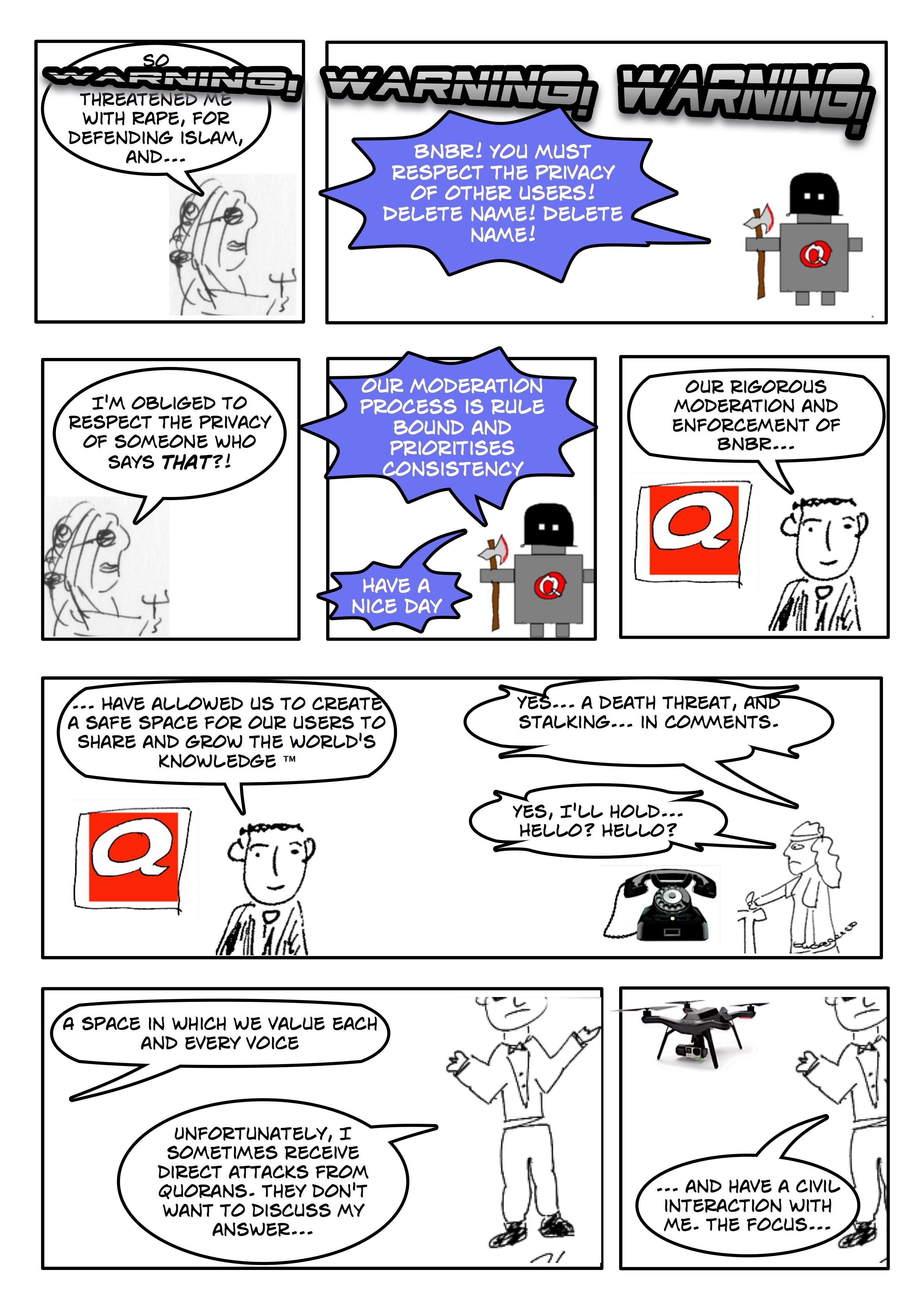

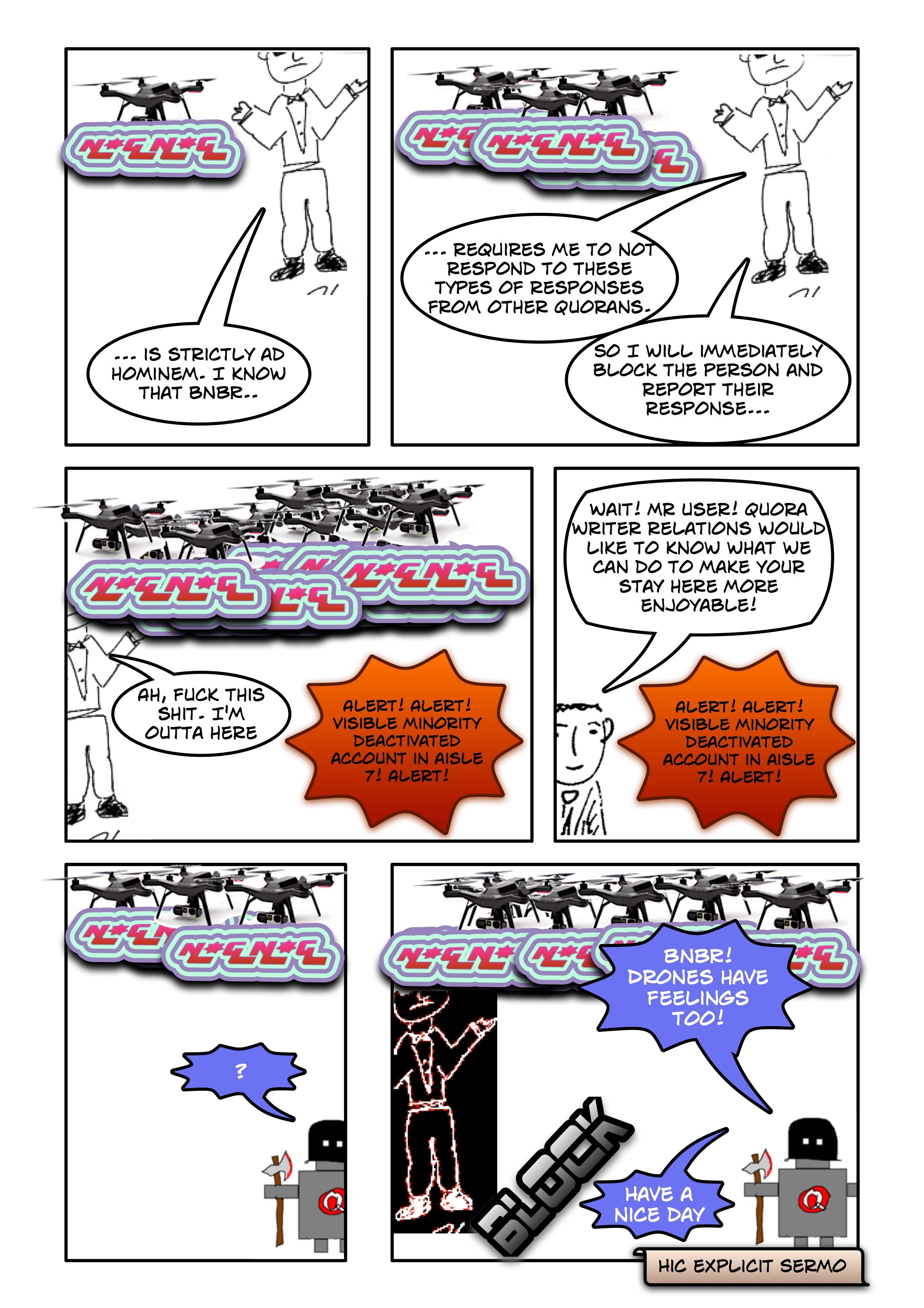

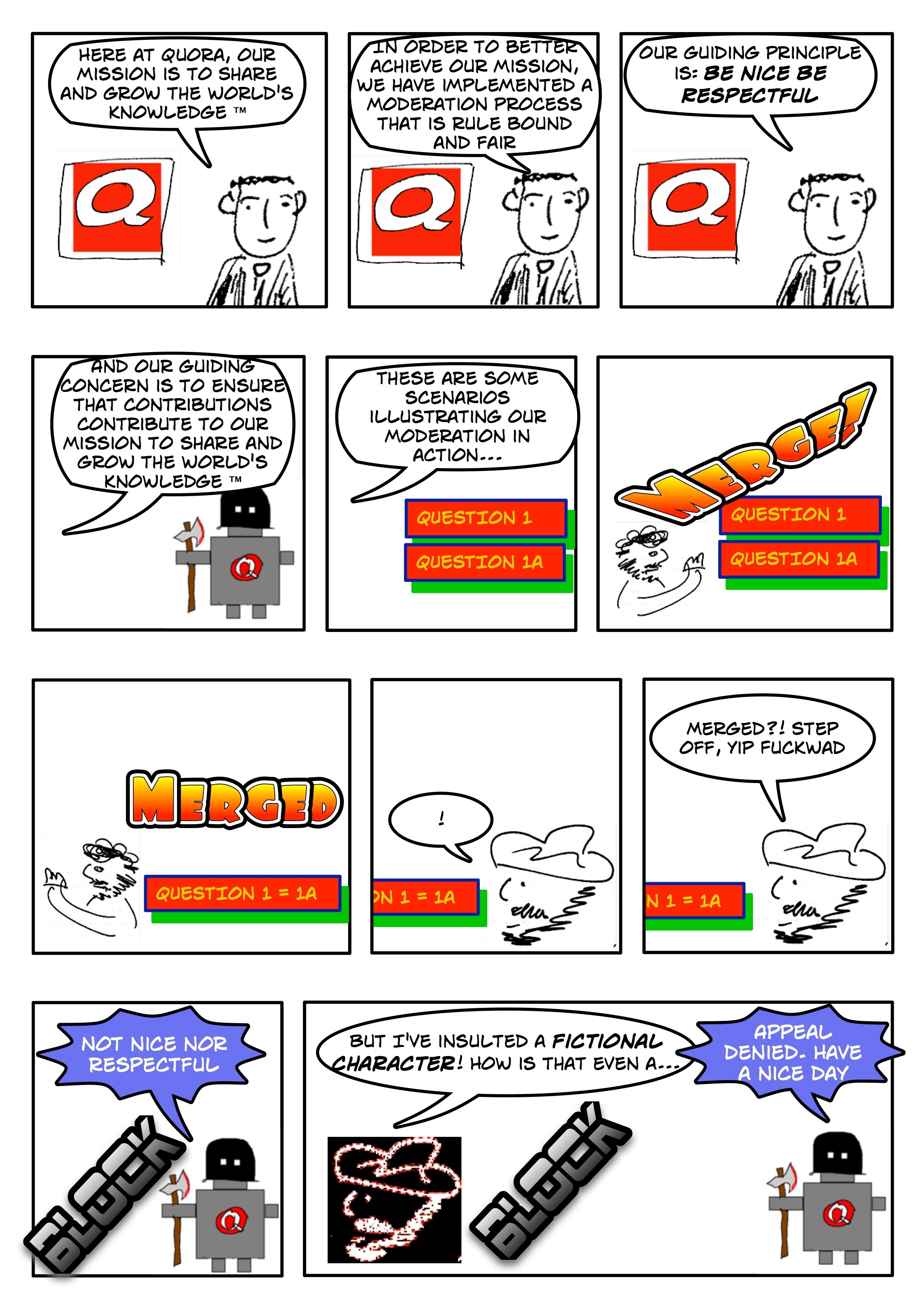

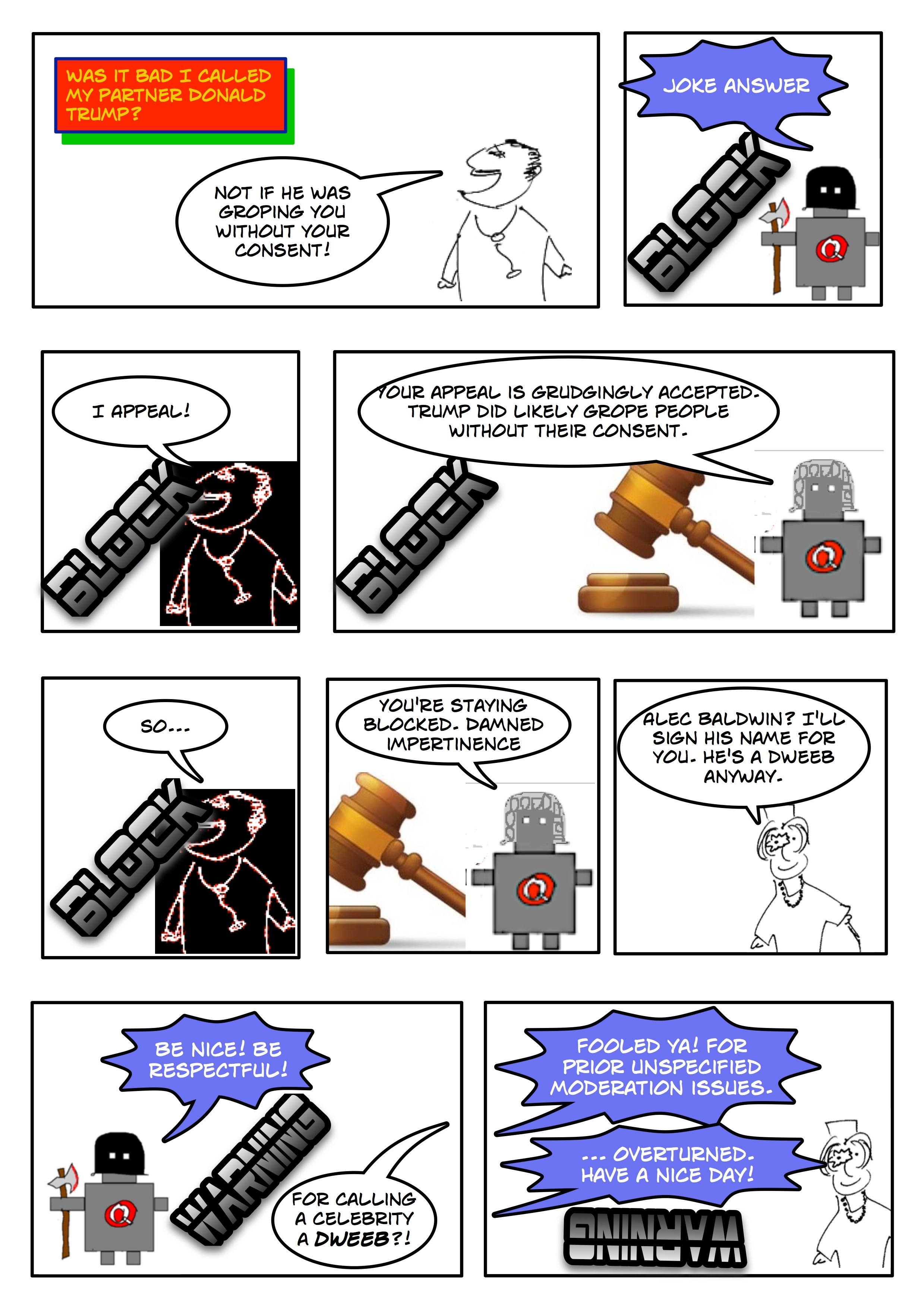

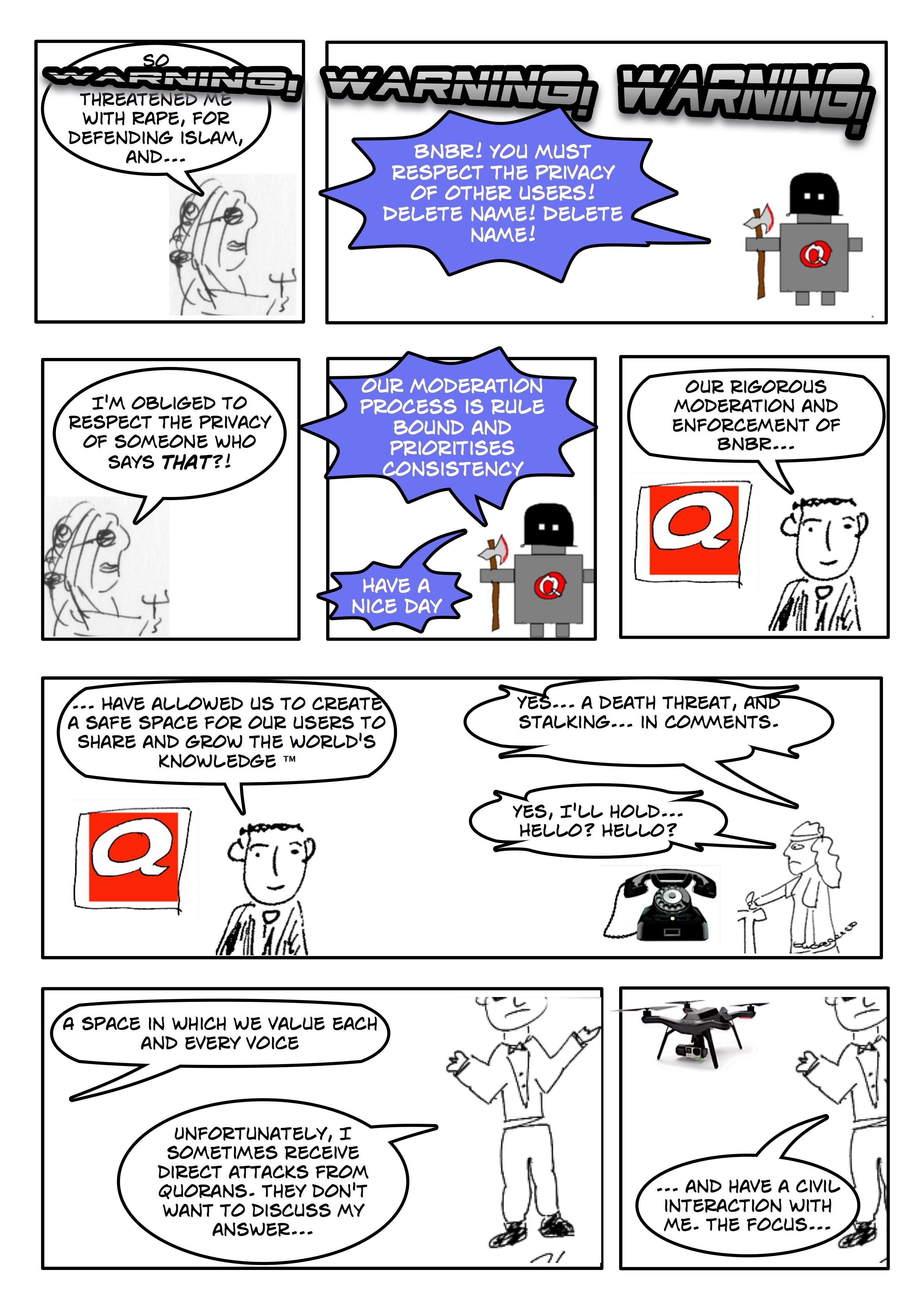

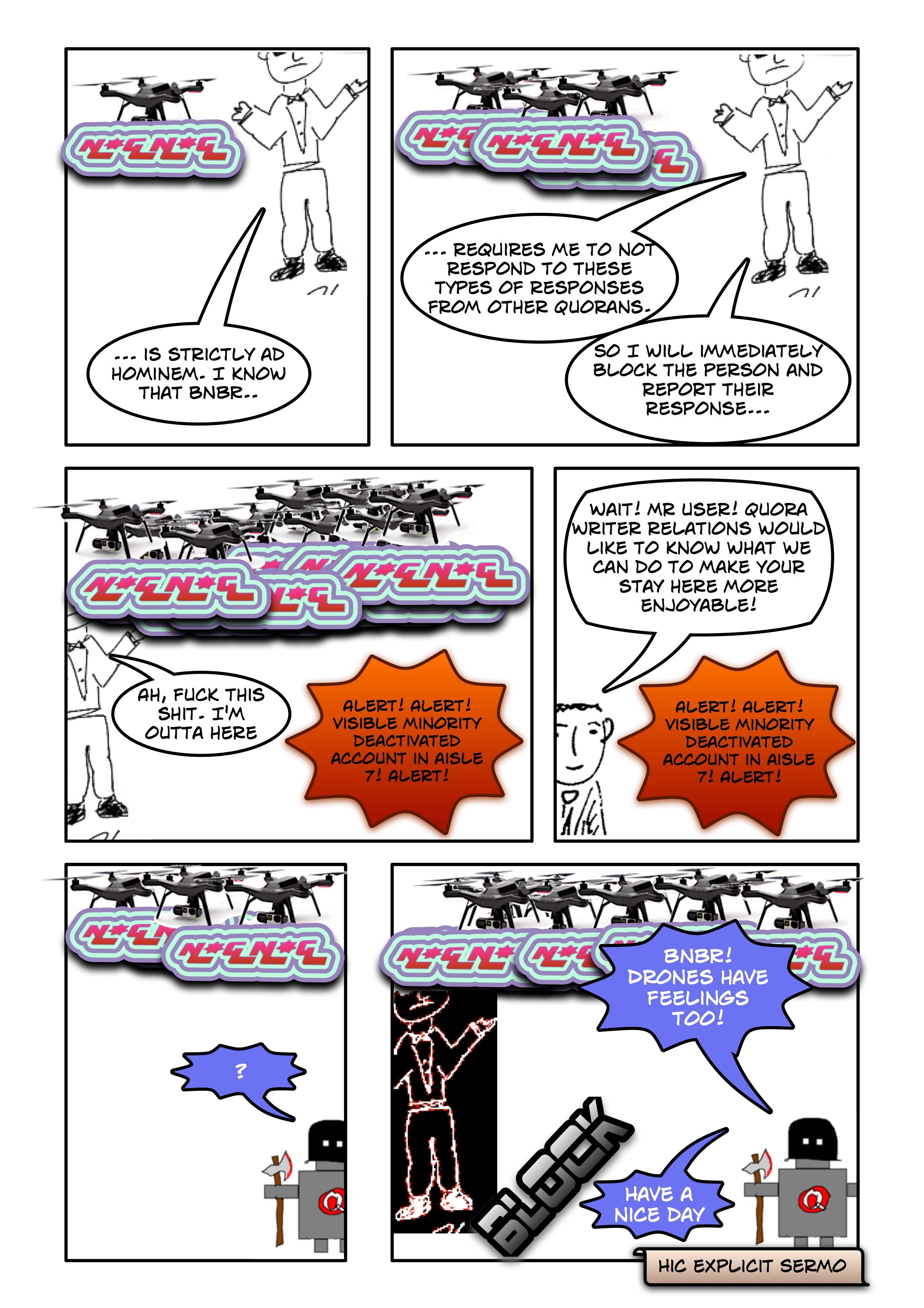

Not quite in the Rage Comic genre, but I’m rather proud of what I came up with as a lowercase rage comic in this post:

Not quite in the Rage Comic genre, but I’m rather proud of what I came up with as a lowercase rage comic in this post:

Didn’t know about the Quora Meme Page, but it’s been inactive for three years anyway.

The Memes of Production blog has just started up. Contributions welcome!

I finally worked this out, by reading half of Ancient Greek accent – Wikipedia. (Reading the other half confirms it, but I’m still proud of myself.)

The answer is: the second element if acute, the first if circumflex.

Let’s take this slow.

The explanation of the distinction between acute and circumflex in the Wikipedia article is based not on contours on a vowel, but on high/low contrast on Morae (what a long vowel has two of, and a short vowel has one of). And I gotta admit, that’s the first time an explanation of Greek accent has made sense to me.

So. Let’s ignore grave. Short vowels can only take an acute. That is a high pitch on a single mora:

έ = ˥e.

A long vowel can take an acute. That is interpreted as a high pitch on the second mora:

ή = ɛ˥ɛ

μή = mɛ˥ɛ

You’re going from neutral pitch to high pitch. That will of course sound like rising pitch.

A long vowel can instead take a circumflex. That is interpreted as a high pitch on the first mora:

ῆ = ˥ɛɛ

In context, a circumflexed vowel is a neutral pitch mora, followed by a high pitch mora, followed by a neutral pitch mora; e.g.

καλῆτε = ka.lɛɛ.te

That will sound like a circumflex: rising then falling.

So. Diphthongs involve two short vowels. (There’s also long diphthongs, which are the things with iota subscripts.)

Two short vowels are two morae.

So it’s the same. αί has high pitch on the second mora (i.e. second vowel):

αί = a˥i

αῖ has high pitch on the first mora (i.e. first vowel):

αῖ = ˥ai

Now, your question was, if we use contour tones rather than pitch peaks, how do we transcribe it in IPA?

At that point, I myself would prefer to just go with convention, and put the contour tone symbol on the second letter, because that’s what Greek does. But the point here is that the contour tone, in both cases, starts on the first vowel = first mora. So arguably putting it on the first vowel is more accurate.

No different to other colloquial registers of English: stressed you is “you”, unstressed you is “ya”.

That’s how Leonard Cohen did all his rhymes with Hallelujah, after all: http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/l…

Not a request, other than a request that we show appreciation to the manumitted gnomes, such as Christopher VanLang, who have permission to reorg locked topics, and act on requests here to do.

Thanks, manumitted gnomes! It’s not a coincidence that the Pileus (hat), which manumitted slaves wore in antiquity, looks like a gnome cap:

File:Man pilos Louvre MNE1330.jpg – Wikipedia ; see also Phrygian cap – Wikipedia.

To expand on Edmond Pano’s answer:

Indo-European languages are not all that similar to each other. That’s why it took so long to establish the family. (It was much more obvious in Classical times, but people in Classical times weren’t paying attention.) The level at which laypeople can tell similarities is at the branch level.

So Danish isn’t from outer space if you’re aware of German, and Spanish isn’t from outer space if you’re aware of Italian, and Czech isn’t from outer space if you’re aware of Bulgarian. (Notice I didn’t mention French and English, which are still quite odd.)

But an isolate branch like Albanian or Armenian is going to stand out, because there’s no immediately close language. In fact the only reason why we don’t say that about Greek more is that people at large are already a little familiar with Greek, because of its cultural influence.

If you’re Greek or Macedonian, however, and leaf through an Albanian grammar, it doesn’t look different at all: the Balkan Sprachbund has made its grammar very close to its neighbours. And if you work out the sound changes, it’s surprising how much of the Albanian vocabulary is chewed-up Latin.

Start with Byzantium: Orthodox Christianity was the state religion, and heterodoxy was deemed treason. Jews and Muslims were tolerated in Byzantine Law as second class citizens; heretical Christians got the sword.

In the Ottoman Empire, that continued with the Rum millet: Greek Orthodoxy defined the nation of Romans, which was considered to include Greeks. Catholicism was a minority presence in Greece, and Greek Catholics were deemed not Rum (Romioi, Romans), but Frenk (Frangi, Franks).

When the Modern Greek State was founded, Orthodoxy became the state religion quickly; and it was considered coextensive with Greek national identity. That has allowed it a hegemony that Western Europeans are uncomfortable with; the Church of Greece gets veto, for example, on building places of worship for any creed, which is why there still isn’t a mosque in Athens. Is the 180 Year Wait for an Official Mosque in Athens Finally Over?

Catholics were ignored, and they were small enough in numbers that they could be ignored. Muslims were Turks as far as everyone was concerned, whatever their ethnicity (Turkish, Gypsy, Greek, or Albanian). Armenians were foreigners. There was some Protestant missionary activity in Greece; the Ottomans considered them a distinct millet, and the Greeks… well, the Greeks ignored them too, just like they ignore Jehovah’s Witnesses.

So, partly history, partly construction of national identity, partly privileged role of the state religion.

Feh. Screw that guy.

I wrote why on my website, something like 20 years ago (ignore the update date): Anti-Chomsky: English. I was somewhat aghast around 2000, when David Horowitz got in touch with me, asking for permission to quote me.

I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about him. (Chomsky, I mean. But not Horowitz either, for that matter.) But:

Like others, I’ve only noticed it this past couple of days.

I get questions from A2As, from my feed, and from questions that people I follow answer. I don’t anticipate using it that much; my followees are pretty disparate, and the people I share interests with are not shy about A2A’ing me.

This won’t be good, for the reasons Alberto Yagos said.

The Greek for bit is: Bit – Βικιπαίδεια. Of course. There is a Hellenic coinage recommended by the Greek Standards Organisation: δυφίο dyphio[n], from dyo “two” and psēphion “digit”. The Ancient Greeks didn’t do portmanteaux, which is what this is; but if you want a Hellenic bit, that’s what’s on offer.

So you *could* go with dyphionomisma, where nomisma is a coin.

But honestly, Bitcoin shouldn’t be translated, not only because it is anachronistic, as Katharina Sikorski argues, but because it s a proper name, not a generic term.

Blockchain? I would do back to literal rendering. Chain of ledgers would be Catena Calendariorum—where a calendarium was not originally a calendar, but a ledger. You could say that the calendarium is virtual, but really, Catena Calendariorum is plenty long already.