Gott sei dank! This is going to be fun!

Ligatures

OK, I’ll dispense with the “other things” (ligatures) quickly, referencing my own page Other Ligatures

There was a mess of ligatures in Greek typography up until the 18th century, because Greek typography was based on late Byzantine squiggle. (That’s why typographers sigh at what might have been after the first 50 years of Greek typography.) The only two ligatures to survive the cull into the 19th century were stigma (στ) and omicron-upsilon (ου). These originated in Byzantium, as did all the other ligatures, and they’re still de rigeur in icons.

Only omicron-upsilon has survived into the 20th century (and I’m assuming the 21st), and it has an interesting survival. To quote a renowned authority (me):

It is never used in print in a book. In the media it might appear on occasion in a headline in a sports paper, and inside the handwritten speech bubble of a political cartoon; but it does not appear in comic books. If a student uses it in school, it will be marked wrong. It will appear in graffiti a lot (as well as on signs put up by neighbours objecting to parking or dumping garbage outside their door). If any shopfront is going to use it, it is going to be a car mechanic’s. It appears in church on the icons (which are revivalist Byzantine), but not in the hymnals or the bibles. It may turn up on old street signs, but certainly not on the newer road signs indicating distances to the next city.

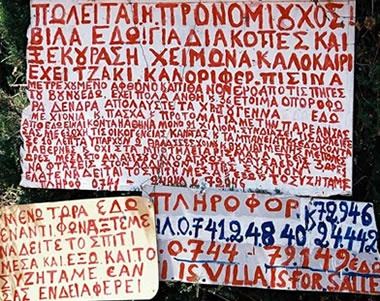

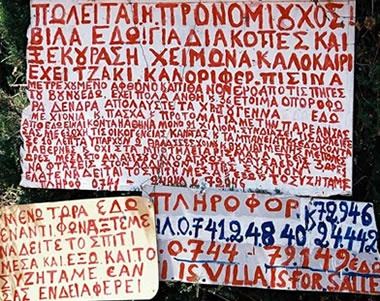

In other words, in Modern Greece this is a consciously casual glyph, which has no official status, and is rarely if ever anything but handwritten. […] although it appears on church walls and in all books printed before the 19th century, the glyph increasingly has a rebellious air around it, expressing contempt for the official glyphs and the establishment promulgating them […] This is why the ligature might have been acceptable on street signs dating from the ’30s, but not on road signs dating from the ’70s. Including a codepoint for it for modern use would not go down well: the point of its modern use, in a way, is that it is not to be found on a keyboard. The following improvised For Sale advertisement for a holiday house illustrates the OU-ligature in its modern natural environment (which, as you’ll notice among the blue daubed-in phone numbers, also pays host to the kai ligature).

Monotonic

Spelling reforms featuring monotonic accentuation, or no accent at all, have been kicking around since the 19th century. They were marginal then, but gradually picked up steam among demoticists. One of the early cause celebres was the classicist Ioannis Kakridis (famous for his school co-translation of the Iliad) being fired from Athens Uni, for reprinting a lecture in monotonic, in the so-called “Trial of Accents”.

It wasn’t just that he was fired. It’s that he was fired in 1941. When you’d have thought Athens Uni had more constructive things to do.

Polytonic accentuation, which was always a nuisance and ill-fitting for Modern Greek, was undergoing simplification all the while. By the 1960s, breathings on rho, graves and iota superscripts had been abandoned. More intellectuals were starting to promote the monotonic, though it still had no official status.

The tipping point, from my vantage point as a precocious preteen, was the press moving across to a de facto monotonic in the 1970s—not so much because they were in the linguistic vanguard, as because they were sick of paying for extra squiggles. A lot of book publishing in the 1970s was also de facto monotonic.

De facto monotonic was not well regulated. Some of it used an agnostic breathing, as well as an agnostic accent. Because the accents were agnostic, the default was a vertical wedge or a dot, rather than an acute. (In fact, dot is what I still use in handwriting.)

There were systems with rules promulgated by various authorities. Emmanuel Kriaras was maybe the most renowned, and his system was different to what has prevailed. Most notably, he used dashes to connect enclitics to words, which resolves an ambiguity between “my” and “to me”. An ambiguity the official system handles horribly, with its optional use of disambiguating accent. And he accented monosyllabic content words.

Kriaras was certainly on the committee for what the official monotonic system should be, but he got outvoted. (And he acquiesced of course; his Early Modern Greek dictionary shifted from polytonic to his monotonic to official monotonic.) The system was decided by committee, and you can tell: many of its choices are mushy compromises (optional this, optional that), rather than unambiguous rules, and rather than phonologically informed notions of stress. (Hence the default of unaccented monosyllabic words.)

Pro-Polytonic web sites will tell you that monotonic was sprung on the unsuspecting Greek people by a midnight parliamentary session in 1982. Much Greek legislation is; what was rather more significant is that the move had bipartisan support, and from memory was implemented quite smoothly in education and the media. I was in 5th grade, and the relief all around was palpable.

The dot or wedge continued in use long enough to be confusing to early versions of Unicode, which differentiated the “tonos” (accent) from the acute. Since 1986. the monotonic accent has officially been the acute.

Monotonic has become more and more entrenched in the decades since. Early Modern Greek text is now increasingly being published in monotonic as well, although the rules have to be adjusted to allow for monotonic accent of ambiguous monosyllabic ancient words (e.g. ὁ vs ὅ). Estia newspaper used to be the last refuge of Katharevousa; now it is the last refuge of the polytonic. The polytonic has shifted from being a marker that you’re middle aged, to a marker that you’re conservative.