Procopius, de Bellis I xx:

At about the time of this war Hellestheaeus, the king of the Aethiopians, who was a Christian and a most devoted adherent of this faith, discovered that a number of the Homeritae on the opposite mainland were oppressing the Christians there outrageously; many of these rascals were Jews, and many of them held in reverence the old faith which men of the present day call Hellenic. He therefore collected a fleet of ships and an army and came against them, and he conquered them in battle and slew both the king and many of the Homeritae. He then set up in his stead a Christian king, a Homerite by birth, by name Esimiphaeus, and, after ordaining that he should pay a tribute to the Aethiopians every year, he returned to his home.

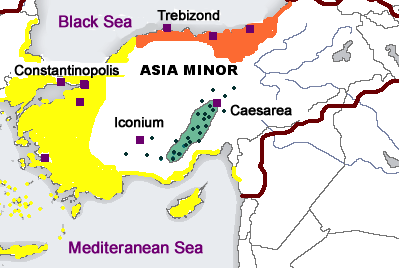

Hellestheaeus was Kaleb of Axum, king of Axum (northern Ethiopia) in 520.

The Homeritae are the Himyarite kingdom, around Yemen, which fell to Axum in 525.

Esimiphaeus (Sumuafa’ Ashawa’) was the Christian Himyarite viceroy appointed by Kaléb.

The Himyarite kings adopted Judaism around 380, probably for reasons of political neutrality. Per Wikipedia,

From the 380s, temples were abandoned and dedications to the old gods ceased, replaced by references to Rahmanan, “the Lord of Heaven” or “Lord of Heaven and Earth”

…

During this period, references to pagan gods disappeared from royal inscriptions and texts on public buildings, and were replaced by references to a single deity. Inscriptions in the Sabean language, and sometimes Hebrew, called this deity Rahman (the Merciful), “Lord of the Heavens and Earth,” the “God of Israel” and “Lord of the Jews.” Prayers invoking Rahman’s blessings on the “people of Israel” often ended with the Hebrew words shalom and amen.

Now, Procopius is claiming that paganism continued in Himyar, despite Judaism being the state religion. Paganism certainly wasn’t extinguished immediately. In telling of the early Jewish king Abu-Kariba (390–420), Wikipedia recounts:

Initially, there was great resistance, but after an ordeal had justified the king’s demand and confirmed the truth of the Jewish faith, many Himyarites embraced Judaism.

Yet

After Abu-Kariba’s demise (420), a pagan named Dhū-Shanatir seized the throne.

I know nothing of the history of the Himyarites, or of Yemeni archaeology. Yet, even if paganism was no longer the official religion, I see no problem with some Himyarites continuing to be pagan.