- The allusions. Which are much more obvious in Ancient Greek, because it had several quite distinct literary dialects. If you want to allude to Homer, or to the tragedians, you can easily choose a word that occurs only in Homer, or a grammatical inflection that is antiquated. And literate Ancient Greeks were meant to be across all the canonical texts; so one adjective can invoke an entire myth. (It’s no different in our contemporary cultures; we just have different canons.)

- The convoluted syntactic structures: how, at its best, a prose sentence is a poised, beautiful construct, with lots of nesting and embedding and qualifications and rhetorical contrasts. And at its worst, it’s a rambling, ugly jumble, with lots of nesting and embedding and qualifications and rhetorical contrasts. We don’t write like that any more, and more and more, we don’t read like that any more. Not necessarily a bad thing, just different.

- The subtlety of free word order; something I miss in translation from Modern Greek as well. Free word order isn’t just an excuse to put syntax in the blender (at least, it isn’t in prose); it’s a way of making nice, understated distinctions in emphasis, or contrast, or in topic vs comment structures in the sentence. English does that as well, of course, but with different means: there’s a reason plaintext English still feels it needs to use all caps or asterisks for emphasis, and Greek doesn’t.

- The kind of primitive way Classical Greek deals with abstractions: it’s not Goodness, it’s The Good; not Equality, but The Equal. In fact, old technical Greek seems to make do with some surprisingly sparse resources.

Month: September 2016

What are major languages which declined/extinct during Turkification of Anatolia?

All the answers posted are very good, and a more substantial contribution than I will make. I agree that in all likelihood, by the time the Seljuks came to town, the indigenous Anatolian languages were long gone, and it was all about the retreat of Greek and Armenian. But I was A2A’d.

So I’ll talk about Greek.

What do I know? I’ll draw on the survey in Modern Greek in Asia Minor; a study of the dialects of Siĺli, Cappadocia and Phárasa, with grammar, texts, translations and glossary : Dawkins, R. M. (Richard McGillivray), 1871-1955.

- The collapse of Greek language and Christianity in Western Asia Minor in the 13th century appears to have been quite rapid: a matter of generations.

- Though I haven’t seen solid evidence for this, it seems that the substantial Greek populations in the Western Asia Minor coast date from Ottoman times, with Greeks settling the coast from the nearby islands. The dialects of the coast are certainly close to those of the Aegean islands. Dawkins concurs, speaking of both settlement from the islands, and a wave of migration out of Greece in the 18th century.

- We know that Bithynia was resettled by both Greeks and Bulgarians in the 1500s–1600s. In fact, there was even a Tsakonian colony on the mouth of the Gönen river, which probably dates from the 1700s.

- I think the Greek population in European Turkey was continuous.

- The Greek population in the Pontus was continuous, and if anything expanded, with mining colonies reaching far into the Black Sea hinterland: Ak Dağ, Buğa Maden, Bereketli Maden, Nevşehir, Ürgüp, Keban Maden, and around Şebinkarahisar.

- There were two distinct regions where Cappadocian Greeks lived: 6 villages around Pharasa, and 20 villages in Western Cappadocia. The language had substantially retreated by the time Dawkins surveyed them in situ; most Christians in the region already spoke Turkish, and particularly in South Western Cappadocia (e.g. Ulağaç), the Greek spoken was heavily influenced by Turkish.

- There was isolated Greek-speaking communities in Livisi (Kayaköy near Fethiye), the town of Sille near Konya, and a dialect that had died out by 1900 in Gölde of Lydia (near Kula, Manisa).

So, tl;dr:

Greek was vibrant in the Pontus; retreating in Cappadocia (and anecdotally the other remaining old settlements as well, with the possible exception of Livisi); and wiped out everywhere else in Anatolia though Turkification; the substantial Greek-speaking population in Western Asia Minor was the result of later resettlement.

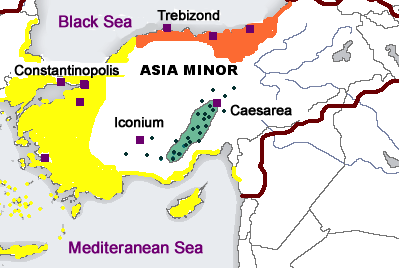

I’m pretty sure this map from Wikipedia (File:Anatolian Greek dialects.png) is overstated for both Cappadocian and Mainstream Greek, but it’s a start:

Was the Greek population in western Asia Minor continuous from Byzantium, or did it migrate back to Asia Minor in Ottoman times?

Motivated by discussion with Dimitra Triantafyllidou at Nick Nicholas’ answer to What are major languages which declined/extinct during Turkification of Anatolia?

Citing from discussion there:

The received wisdom, from:

- Vryonis, Speros, Jr. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

is that the bulk of Asia Minor was islamised and turkicised relatively quickly after the movement of the Turks into the region.

It seems that the substantial Greek populations in the Western Asia Minor coast date from Ottoman times, with Greeks settling the coast from the nearby islands. The dialects of the coast are certainly close to those of the Aegean islands. Dawkins concurs, speaking of both settlement from the islands, and a wave of migration out of Greece in the 18th century.

- Dawkins, Richard McGillivray. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor; a study of the dialects of Siĺli, Cappadocia and Phárasa, with grammar, texts, translations and glossary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

We know that Bithynia was resettled by both Greeks (from Epirus) and Bulgarians in the 1500s–1600s. In fact, there was even a Tsakonian colony on the mouth of the Gönen river, which probably dates from the 1700s.

Was Procopius referring to second half of 6th century, when he says that “some of these rascals were still Animists” or much earlier times in Arabia ?

Procopius, de Bellis I xx:

At about the time of this war Hellestheaeus, the king of the Aethiopians, who was a Christian and a most devoted adherent of this faith, discovered that a number of the Homeritae on the opposite mainland were oppressing the Christians there outrageously; many of these rascals were Jews, and many of them held in reverence the old faith which men of the present day call Hellenic. He therefore collected a fleet of ships and an army and came against them, and he conquered them in battle and slew both the king and many of the Homeritae. He then set up in his stead a Christian king, a Homerite by birth, by name Esimiphaeus, and, after ordaining that he should pay a tribute to the Aethiopians every year, he returned to his home.

Hellestheaeus was Kaleb of Axum, king of Axum (northern Ethiopia) in 520.

The Homeritae are the Himyarite kingdom, around Yemen, which fell to Axum in 525.

Esimiphaeus (Sumuafa’ Ashawa’) was the Christian Himyarite viceroy appointed by Kaléb.

The Himyarite kings adopted Judaism around 380, probably for reasons of political neutrality. Per Wikipedia,

From the 380s, temples were abandoned and dedications to the old gods ceased, replaced by references to Rahmanan, “the Lord of Heaven” or “Lord of Heaven and Earth”

…

During this period, references to pagan gods disappeared from royal inscriptions and texts on public buildings, and were replaced by references to a single deity. Inscriptions in the Sabean language, and sometimes Hebrew, called this deity Rahman (the Merciful), “Lord of the Heavens and Earth,” the “God of Israel” and “Lord of the Jews.” Prayers invoking Rahman’s blessings on the “people of Israel” often ended with the Hebrew words shalom and amen.

Now, Procopius is claiming that paganism continued in Himyar, despite Judaism being the state religion. Paganism certainly wasn’t extinguished immediately. In telling of the early Jewish king Abu-Kariba (390–420), Wikipedia recounts:

Initially, there was great resistance, but after an ordeal had justified the king’s demand and confirmed the truth of the Jewish faith, many Himyarites embraced Judaism.

Yet

After Abu-Kariba’s demise (420), a pagan named Dhū-Shanatir seized the throne.

I know nothing of the history of the Himyarites, or of Yemeni archaeology. Yet, even if paganism was no longer the official religion, I see no problem with some Himyarites continuing to be pagan.

No one likes short answers, but nobody reads long answers. What is the best length for an answer?

Is there an ideal answer length on Quora?

This is a topic Laura Hale has had much to say about. Here’s a dump:

- The 1,000+ upvoted answer and its word count by Laura Hale on quora numbers

- Writing longer content for upvotes by Laura Hale on quora numbers

- Super brief look at wordcount and upvotes correlation by Laura Hale on quora numbers

- With your endorsement, I will boldy write long answers for top ranked answer placement by Laura Hale on quora numbers

- How, Is, What, Why my answers!: A think on length and other variables and how I’d do Quora’s ranking algorithm by Laura Hale on quora numbers

In which ports of the Black Sea can we find older people that still speak Greek?

Pontic Greek is still spoken in the Of valley, Turkey by Muslims who remained after the population exchanges.

Their Pontic Greek is distinctive in retaining Ancient Greek /uk/ for “not”; Christian Pontic had truncated it to /kʰ/.

Did Hebrew affect all languages in the world? If so, is it the only language that affected all languages?

… The only wide-ranging influence of Hebrew I can think of is

- In the variants of languages that are spoken by Jews: Yiddish, Ladino, Judaeo-Greek, Judaeo-Persian, Judaeo-Arabic… for all I know, Judaeo-Chinese.

- In the church register of languages impacted by Christianity. And not a lot of words there. Amen, Satan and Sabbath are probably the most wide-ranging ones.

Be careful not to conflate Hebrew with other Semitic languages. In Greek, arrabōn for “pledge; (later) engagement” dates from Classical times; that means it’s not Hebrew, it’s Phoenecian. The same is likely true for camel, which was used by Herodotus.

Both Jews and Christianity spread widely, but the lexical impact of Hebrew, I’d say, is surprisingly superficial. English, Greek and Latin have gotten around a lot more.

Which gorgeous English unisex name means”Royal Castle in a forest clearing”?

… Another episode of Quora Jeopardy!

A clearing is a lea.

A court can be a royal Castle.

… Courtleigh?

EDIT: Kimberly (given name)

What makes diaspora groups such as the Armenians, Jews, etc. so successful? Did the diaspora itself have some marked impact on the culture and trajectories of these groups or is it something else entirely?

A socially marginalised group will not have access to the normal institutional advantages of members of the host society—connections, class privilege, leisure time, cultural familiarity etc. etc. Members of that group will be more highly driven to succeed, to redress those disadvantages.

They will be more strongly motivated to succeed, if they see exemplars of success around them—if some members of the diaspora have already succeeded despite social marginalisation, or if they are intermixed with the host society (not ghettoised), so that they are exposed to paradigms of success from within the host society.

If OTOH they’re ghettoised, and if the diaspora society is insular, so that they are not exposed to paradigms of success—then, not so much. There is less incentive to succeed, if the only experience you have is of failure.

And if the diaspora knows what success looks like, they will use whatever levers the host society does not expressly or implicitly block them from using. Such as public education.

That, btw, is why I did not know any Greeks in Australia doing linguistics when I went to uni. That’s a luxury of established ethnicities. I only started seeing Greeks in linguistics classes when I was lecturing.

What made up Greek term could be used for this pretend medical speciality; “The study and exploration of careers for doctors.”?

I’m going to continue with James Cottam’s coinage, done in comments to James Cottam’s answer to Does this made up Latin/Greek word, Vitaemedology, make sense for the following phrase “The study of careers for doctors.”

iatrurgology ἰατρουργολογία. Doctor work-ology.

But let’s see what others have to say…