I would like to take the opportunity afforded by this question, to translate the epigraph to Ptolemy’s Geography, which is included in the new edition. It might be Byzantine rather than Roman, but for these purposes, Byzantine can serve for Roman. And it illustrates that Romans looked down on all foreigners, not just ones with different-coloured skin.

Ἐν γραμμαῖς τὸν κόσμον ἀριθμηθέντα νόησον·

ἄρκτους, Ὠκεανόν, δύσιν, ἀντολίην τε νότον τε,

χεῖμα, θέρος, φυσικάς τ’ ἀτραποὺς σκολιάς τε κελεύθους,

Αἰθίοπάς τ’ ἀδρανεῖς, Γερμανῶν δύσμορα φῦλα,

Σαυρομάτας χοίροισιν ἐοικότας ἠδὲ καὶ αὐτῆς

αἰνομόρου Σκυθίας χαλεπὸν γένος ἄχρις ἐς ἠῶ,

Ἰνδῶν τε Σηρῶν τε· τὸ γὰρ πέρας ἀντολίης γῆς.Here comprehend the world numbered in lines:

north, Ocean, west, east, south; summer and winter;

the roads of nature and the crooked pathways;

the idle Ethiops; the ill-starred Germans;

and the Sarmatians, who look like pigs;

the irksome race of wretched Scythia;

even unto the daybreak lands, of India

and China, at the eastern edge of Earth.

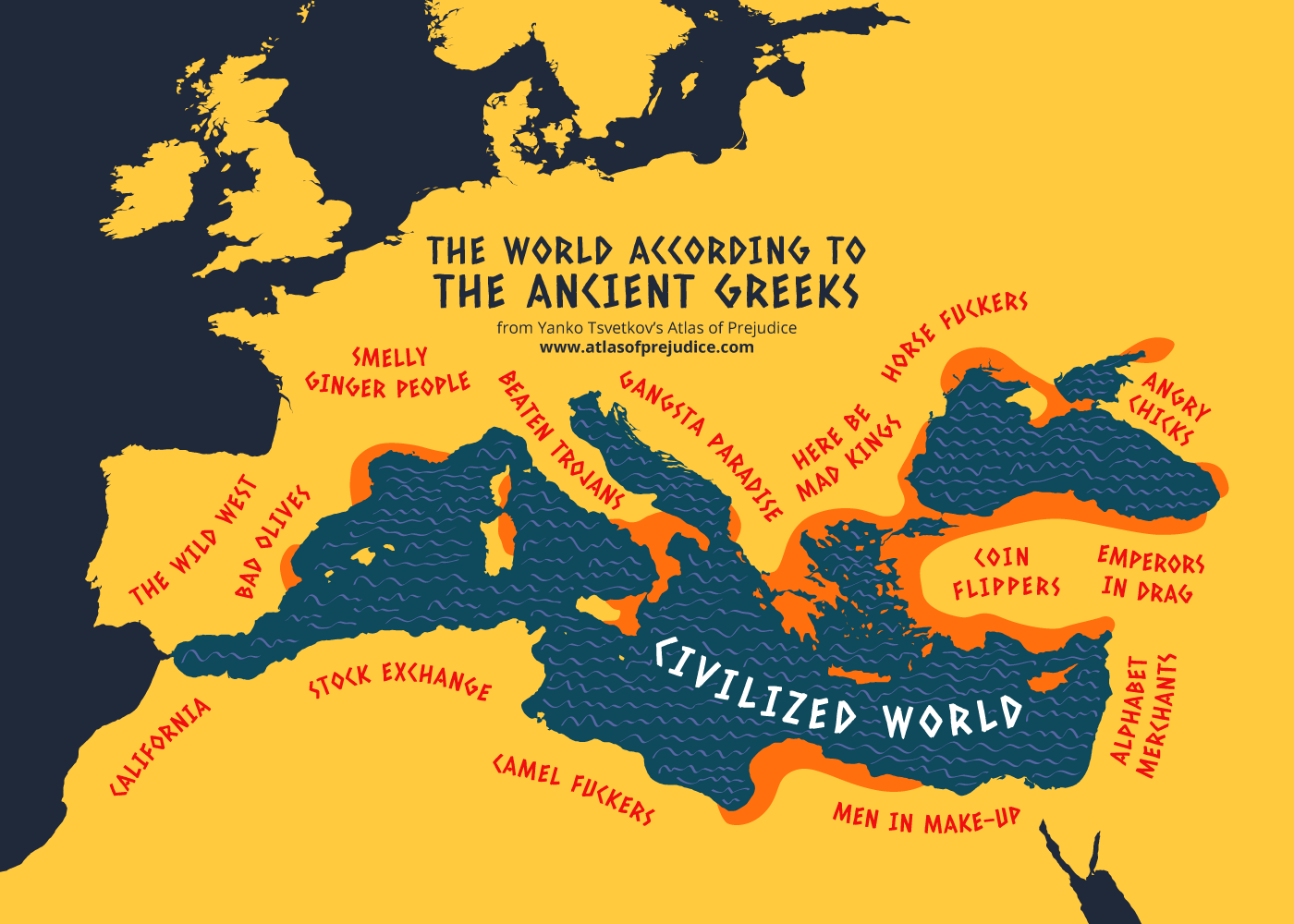

EDIT: as is so often the case, Yanko Tsvetkov’s Atlas of Prejudice nails it: