How many months ago did you A2A me this, Zeibura S. Kathau? I’ve been clearing out my backlog.

The question really is not why isn’t there a Single Modern Latin, but why is there a Single Modern Greek.

- Actually, there is not a single Modern Hellenic language. Under no linguistically informed notion of language is Tsakonian or Southern Cappadocian the same language as Standard Athenian Greek. You have to be damned generous to say Pontic is. And if we’re being honest, basilectal Cypriot is pretty iffy too. But it is still fair to say that there is less diversity within the Hellenic languages than there is within the Romance languages.

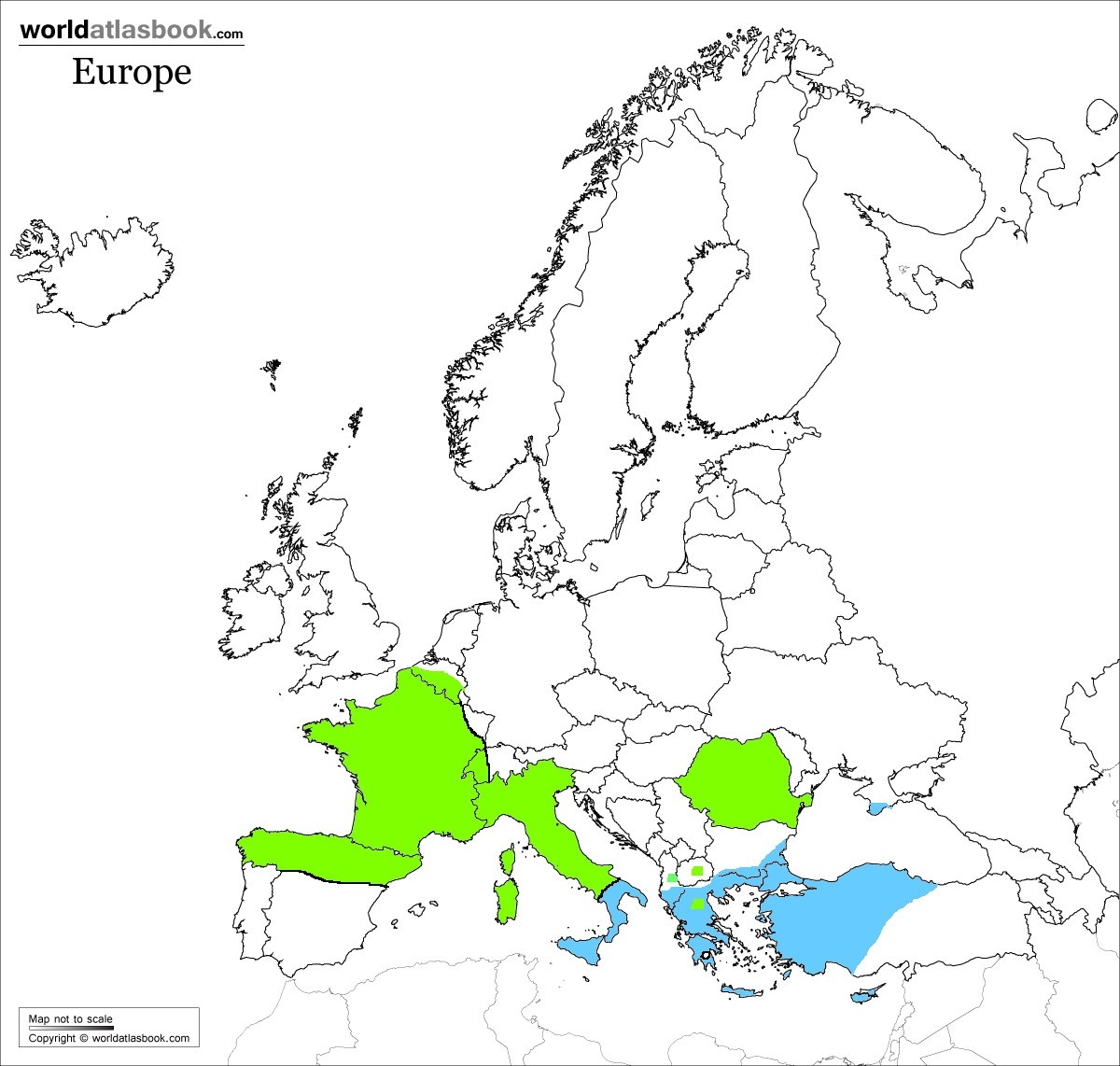

- The area over which Modern Romance languages were spoken historically is much bigger than the area over which Modern Hellenic languages were. Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Romania, patches of the Balkans; vs. Greece, Cyprus, and patches of the Anatolian hinterland [EDIT: and some other bits: see Dimitra Triantafyllidou’s comment]. Greece may have been the Eastern Roman Empire’s lingua franca, but that didn’t hellenise the Slavs or the Syrians.

A rough guess at 800 AD dominion of Romance and Hellenic languages.

- There are lots of substrates at work in Romance, both Celtic and Germanic (and whatever the hell the substrate of Romanian is). That’s a large part of what has differentiated the Romance languages. Now, Greece has had its share of other peoples moving in too, and there’s a lot of adstratal effects on Greek: Greek is a part of the Balkan Sprachbund, especially on the Balkan mainland, and there have been clear contact effects—not all one way. But even though there were clearly substantial hellenised Slavic populations in the middle ages, Greek does not come across as a language with a whole lot of substrate going on.

- Tsakonian does; but Hesseling was pilloried for suggesting it. By town council meeting, no less.

- If an Egyptian Greek had survived, you’d be seeing a lot more substrate effects. They’re certainly quite clear in the papyri.

- The prestige of archaic Greek (particularly church Greek; much later on, written Greek in general) had a profoundly conservative effect on the language, in a way that was different to Western Europe. In fact, the Greek Aromanian linguist Nikos Katsanis has pointed out that the most extreme palatalisations that have happened in Greece were in Tsakonian and Aromanian. Both were so far removed from the language of the Church, that the language of the Church could not have any effect on their pronunciation.

- He left out Lesbos, where there’s been similar hi-jinx. But it’s a nice observation.